At the core of many countries in Africa is community, and that seeps into our art practice. Over decades, from independence-era optimism to creative resistance movements, the mid-20th century saw the rise of artistic clubs, societies, and collectives across Africa. These were not just places to make art; they were passionate forums and incubators of radical ideas, community expression, and cultural independence.

Below, we explore several of the most influential.

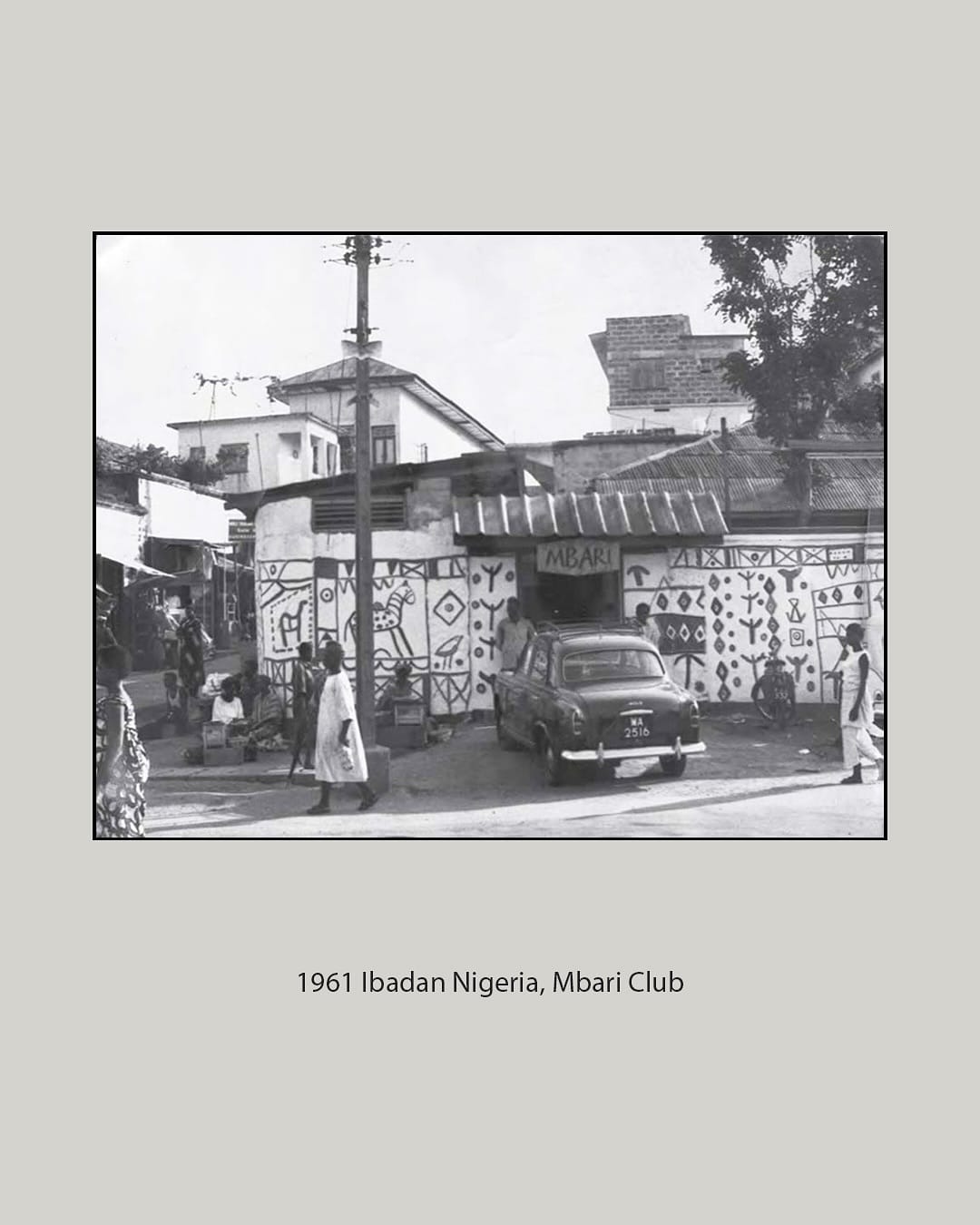

Mbari Artists and Writers Club – Ibadan (Nigeria, 1961)

Founded in Ibadan, Nigeria, in 1961, the Mbari Artists and Writers Club became a vibrant hub for writers, visual artists, musicians, actors, and intellectuals during the early post-independence era. The name Mbari, an Igbo term associated with creation and communal artistic houses, was suggested by Chinua Achebe and pointed to the ethos of creative renewal and collective expression.

Mbari sought to foster a Pan-African cultural exchange, merging literature, visual arts, theatre, and music in a shared space. It provided a platform for African voices to tell their own stories, free from colonial frames.

Founders and core members included Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, Christopher Okigbo, JP Clark, Uche Okeke, Demas Nwoko, Bruce Onobrakpeya, Es’kia Mphahlele, and others. The club also hosted international figures like Jacob Lawrence and Langston Hughes.

Mbari’s multi-faceted activities included theatre and dance performances, poetry readings, music (even early Fela Kuti performances), art exhibitions, and a library. It also operated a publishing arm connected with Black Orpheus journal, amplifying African and African-American literature.

Although the Nigerian Civil War disrupted its momentum, Mbari’s impact on African modernist culture, publishing, and cross-disciplinary collaborations remains foundational. It influenced later artistic spaces and helped legitimise African cultural production on global terms.

Zaria Art Society – Zaria (Nigeria, 1958–1962)

Merging out of the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology in Zaria in 1958, the Zaria Art Society, often called the Zaria Rebels, was a student-led movement reacting against Eurocentric art curricula.

The society promoted “natural synthesis”, blending indigenous artistic traditions (like Uli designs and Nok influences) with modernist forms. It was rooted in a broader post-colonial project of reorienting art towards Nigerian identity.

Artists such as Uche Okeke, Demas Nwoko, Yusuf Grillo, Jimoh Akolo, Simon Okeke, and Bruce Onobrakpeya defined a generation of Nigerian modernists.

Though short-lived (disbanded by 1962), the society deeply shaped Nigerian visual culture and influenced institutional art education and the broader Nigerian modern art movement

Medu Art Ensemble – Gaborone (Botswana, 1979–1985)

Formed in 1979 in Gaborone, Botswana, the Medu Art Ensemble was a multi-disciplinary collective rooted in anti-apartheid resistance and Pan-African solidarity.

Comprising musicians, photographers, graphic artists, writers, and theatre practitioners, Medu worked as “cultural workers” to critique apartheid and support liberation movements in Southern Africa. They produced political posters (often clandestinely circulated), newsletters, exhibitions, music events, and workshops. Its annual Culture and Resistance Festival brought together artists and activists regionally.

Though disbanded violently after an attack in 1985, Medu’s fusion of art and political struggle influenced later cultural resistance and community arts practices across Southern Africa.

Polly Street Art Centre – Johannesburg (South Africa, 1950s–1970s)

In Johannesburg, the Polly Street Art Centre (active through the 1950s–1970s) became a vital training and exchange space amid Apartheid.

Under the leadership of artist Cecil Skotnes from the early 1950s, the centre became a creative crossroads, offering workshops, mentorship, and exhibitions for Black South African artists in a segregated cultural landscape.

Artists such as Sydney Kumalo, Ezrom Legae, Lucas Sithole, and Dumile Feni were shaped here. Though apartheid policies later forced closures or relocations, the centre’s influence persists in South African art histories.

Katlehong Art Society / Art Centre – Katlehong (South Africa, 1969 & 1977)

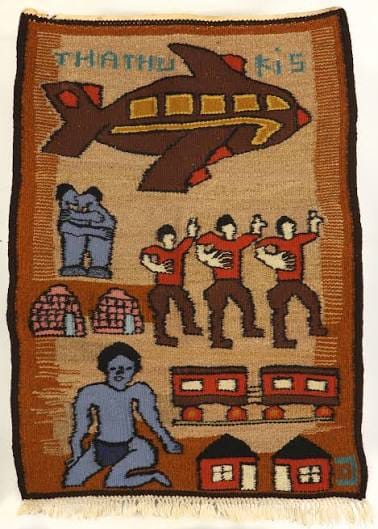

Born from community efforts in Katlehong township near Johannesburg, the Katlehong Art Society was established in 1969 and led to the formal Katlehong Art Centre in 1977.

Emerging from the need for creative spaces under apartheid-era restrictions, the society and centre offered programmes in painting, sculpture, ceramics, weaving, and workshops for local artists.

By nurturing township artists and providing training accessible to youth and community members, Katlehong helped sustain creative practices that countered cultural marginalisation.

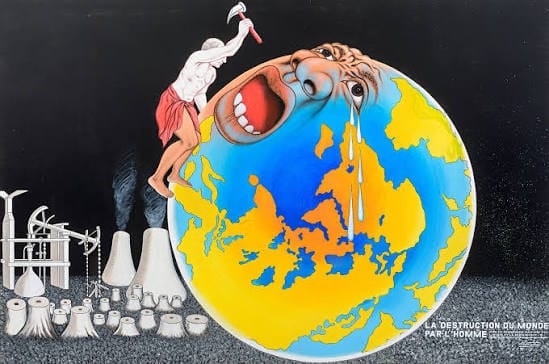

Zaire School of Popular Painting – Kinshasa (DRC, 1960s–1980s)

In Kinshasa (then Zaire), the School of Popular Painting emerged in the late 1950s/1960s, led by artists like Chéri Samba, Moké, and Bodo.

Rather than a formal club, the school formed a loosely-connected collective that made art reflecting everyday life, politics, identity, and social narratives. Its bold use of text and figurative imagery made the work highly didactic and accessible.

This genre influenced broader contemporary African painting by exemplifying how art could directly engage social realities and public discourse.

Thupelo Art Project – South Africa (1985 onwards)

Started in 1985 by David Koloane, Bill Ainslie and others in Johannesburg, the Thupelo Art Project was a workshop-based initiative modelled on the Triangle Network artists’ workshop in New York

“Thupelo” means “to teach by example” (in Sotho). It provided collaborative workshop spaces where local and international artists could share skills, experiment with media, and push creative boundaries beyond apartheid constraints.

Thupelo fostered experimentation, helped establish artist studios like Greatmore and Bag Factory, and strengthened the community through arts dialogue.

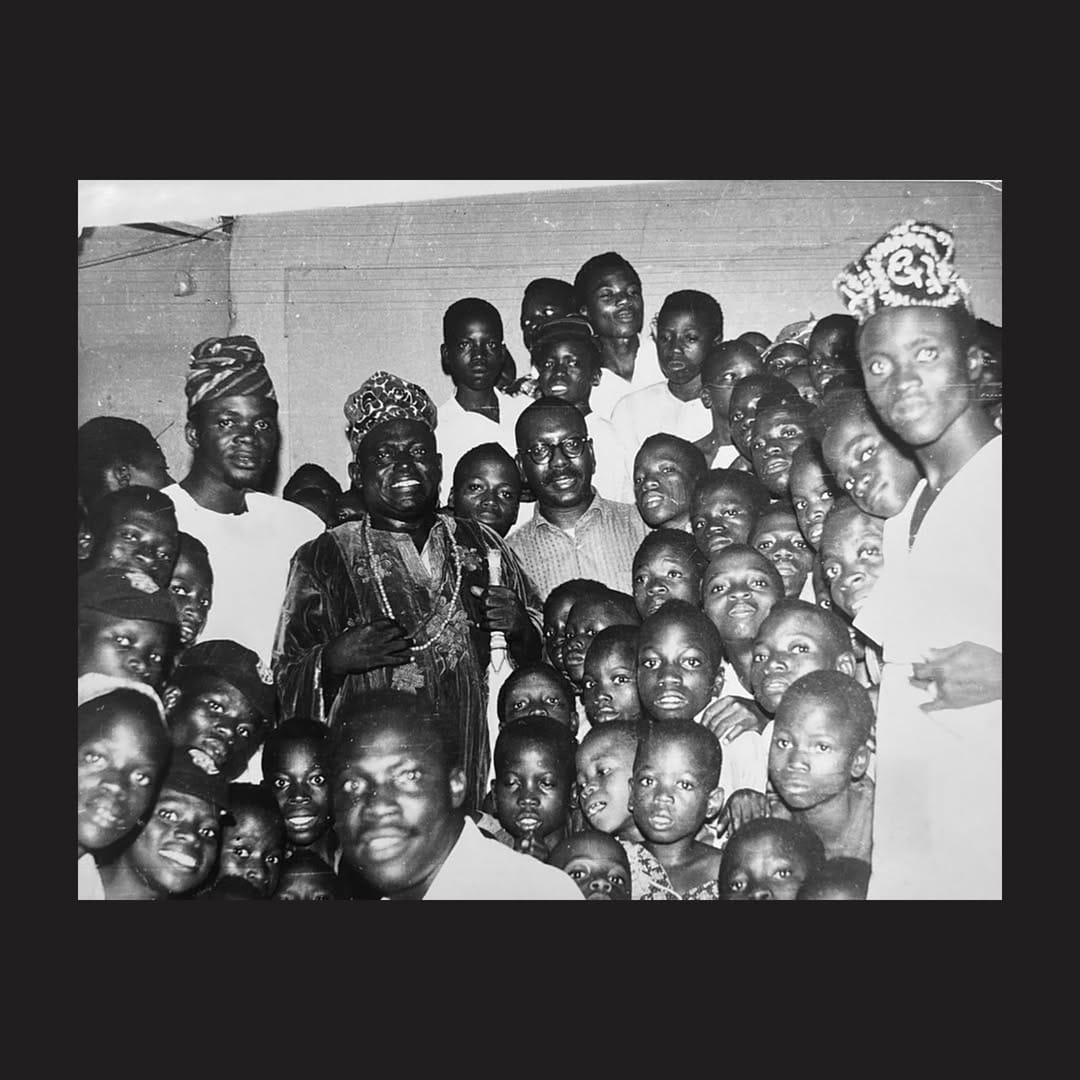

Mbari Mbayo – Osogbo (Nigeria, 1964)

Founded in 1964 in Osogbo, Nigeria, Mbari Mbayo emerged as an offshoot and spiritual successor to the Mbari Artists and Writers Club in Ibadan. While Mbari Ibadan leaned heavily into literary and intellectual exchange, Mbari Mbayo rooted itself more firmly in visual art, performance, and community-based creativity, becoming central to what is now known as the Osogbo Art Movement.

Mbari Mbayo was established as a space for experimentation, cultural preservation, and artistic freedom, particularly for artists outside formal academic systems. It was deeply connected to the encouragement of indigenous Yoruba aesthetics, mythology, and spirituality, while still embracing modern artistic expression.

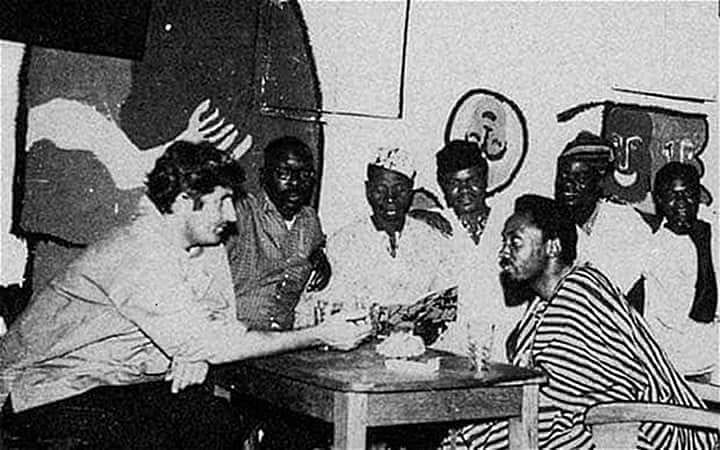

The club was closely supported by Ulli and Georgina Beier, who played a significant role in documenting, mentoring, and promoting Osogbo artists locally and internationally.

Mbari Mbayo nurtured and showcased artists such as Twins Seven-Seven, Muraina Oyelami, Jimoh Buraimoh, Adebisi Akanji, Susanne Wenger, and Bamidele Fakeye (associated with the wider Osogbo circle). Many of these artists went on to sustain decades-long careers, exhibiting globally while remaining deeply rooted in Yoruba cultural forms.

The ethos of Mbari Mbayo centred on art as lived practice, inseparable from ritual, storytelling, music, and communal life. Rather than distancing art from tradition, the collective embraced masquerade, shrine painting, textile experimentation, batik, beadwork, and wood carving as contemporary expressions of heritage.

This approach challenged Western hierarchies of “fine art” versus “craft,” positioning indigenous knowledge systems as intellectually rigorous and creatively expansive.

8 Classic African Films from the ’60s to the ’90s That Still Resonate Today

Honorary Mentions

Kane Kwei Carpentry Workshop – Teshie (Ghana, c.1950s–present)

Founded in the 1950s in Teshie, Accra, the Kane Kwei Carpentry Workshop is one of the most enduring examples of how African craft traditions evolved into globally recognised contemporary art practices. Established by Kane Kwei (1922–1992), the workshop became the birthplace of Ghana’s iconic fantasy coffins, sculptural forms shaped like fish, aeroplanes, cocoa pods, lions, shoes, and everyday objects tied to a person’s life, profession, or aspirations.

Originally rooted in Ga funerary traditions, the coffins were designed to honour the deceased by visually narrating their identity and social role. What began as a deeply local, spiritual craft gradually became a sophisticated visual language, one that bridged ritual, storytelling, sculpture, and design.

The Kane Kwei workshop functioned not as a single-artist studio but as a collective, intergenerational learning space. Apprenticeship was central: skills were passed down orally and practically, reinforcing communal knowledge over individual authorship.

Rather than separating “art” from “craft,” the workshop embodied a worldview where function, symbolism, and aesthetics coexisted. Each coffin was simultaneously utilitarian, ceremonial, and expressive.

After Kane Kwei’s death in 1992, his legacy continued through his nephew Paa Joe, who expanded the workshop’s international reach, followed by subsequent generations of carvers. This continuity underscores one of the workshop’s most powerful contributions: longevity without institutional dependency.

From the 1980s onward, fantasy coffins entered global exhibitions and museum collections, including institutions like the Centre Pompidou and the British Museum. Despite this international attention, the workshop never abandoned its local purpose; funerals in Teshie remained its primary audience.

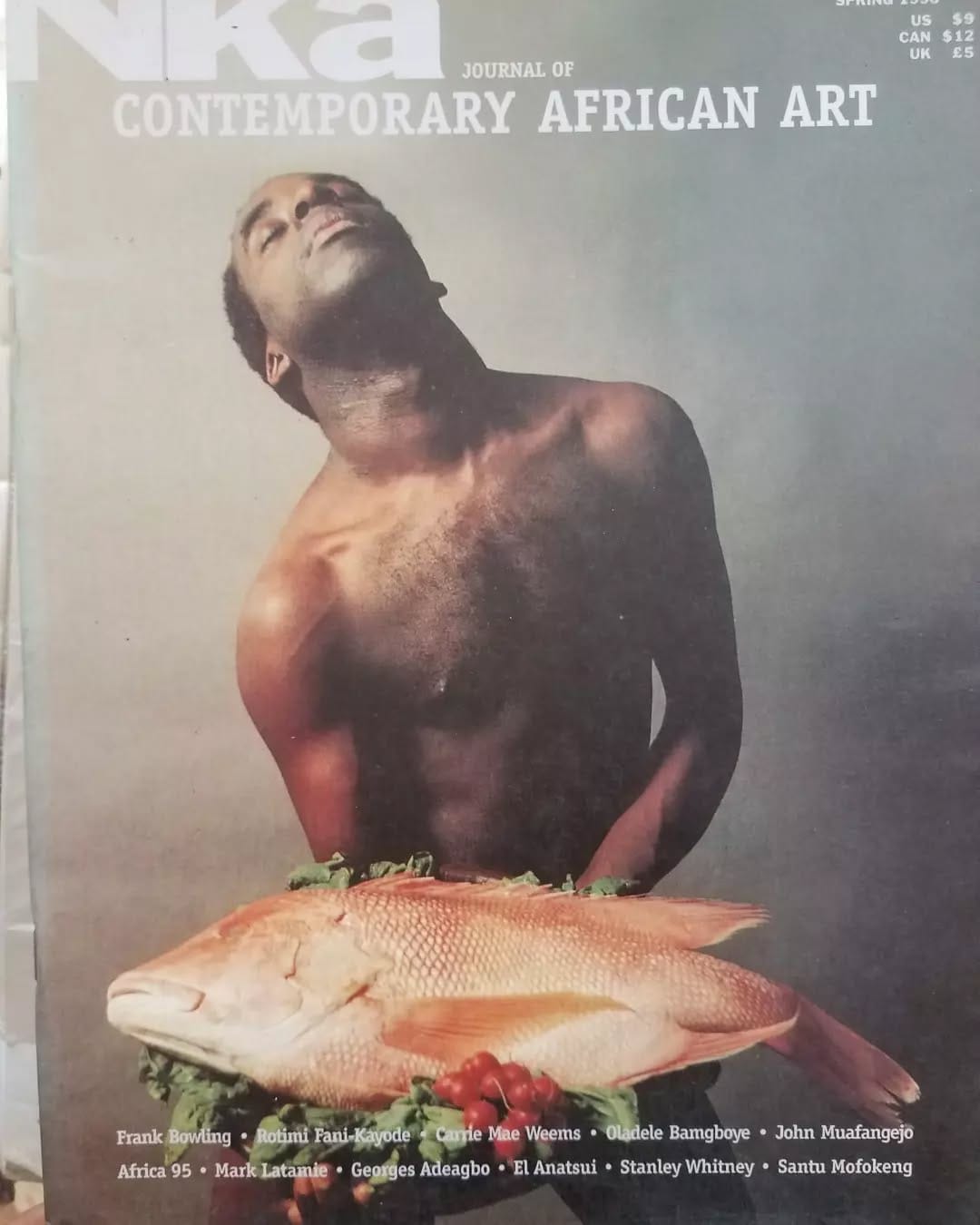

Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art – Founded 1994

Launched in 1994, Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art emerged as one of the most influential intellectual platforms for African and diasporic art discourse. Founded by Okwui Enwezor, Chika Okeke-Agulu, Salah Hassan, and Olu Oguibe, Nka was created at a moment when contemporary African art was gaining visibility but lacked rigorous, self-authored critical frameworks.

Nka was established to provide a space where African artists, scholars, and curators could write their own histories, theories, and critiques, rather than being framed exclusively through Western academic lenses.

The journal foregrounded voices from the continent and the diaspora, treating African art as intellectually complex, politically engaged, and historically situated.

The title “Nka” — an Igbo word meaning art — reflects the journal’s grounding in African epistemologies. Its ethos was unapologetically critical, insisting on nuance, plurality, and debate.

Unlike mainstream art magazines, Nka operated as both a scholarly journal and cultural intervention, blending essays, artist writings, interviews, and critical reviews.

In many ways, Nka functioned like a club or society without walls, a discursive community bound by shared inquiry, debate, and cultural responsibility.

Conclusion

Across continents and decades, African art societies from the ’60s through the ’90s anchored creative communities that demanded self-representation, political liberation, and cultural innovation. Each club, whether a formal society, or workshop project has left an imprint on artistic practice and identity that continues to inform African creative narratives today.

Member discussion