When we talk about architecture, we often reach for the visible: concrete walls, steel beams, soaring towers. But what happens when we let go of those conventions? What if we begin with earth? With rhythm? With memory? What if space isn’t something to simply enter but something to feel, hear, and remember?

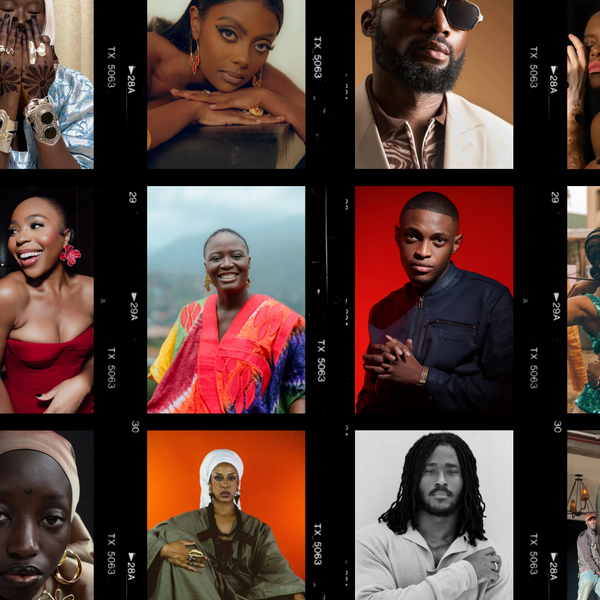

In Earth, Memory and the Spaces We Inhabit, the inaugural exhibition by Black Females in Architecture (BFA), presented in collaboration with DēpART for the 2025 London Festival of Architecture, we’re invited to radically reimagine what architecture means and who gets to define it.

This exhibition doesn’t just ask us to look at buildings. It asks us to listen to the women who shape them long before the first brick is laid.

The Ground We Stand On: Redefining Architecture from the Earth Up

Held at NOW Gallery, the exhibition is rooted, quite literally, in African soil and sensibilities. The architectural structures housing the show draw from traditional West African circular buildings made from earth, often by women. Their terracotta forms, finished in clay-based paint, evoke warmth, continuity, and care. But this isn’t nostalgia. It’s a strategy of survival and vision.

In a field where Black women remain critically underrepresented, comprising less than 0.5% of licensed architects in the UK, this show is filling a gap and rebuilding the frame entirely. Earth, Memory and the Spaces We Inhabit critiques the system and offers an alternative blueprint, grounded in matrilineal values and lived Black experience.

The project emerged from The Ma Project, a research-led inquiry into Black womanhood, spatial care, and intergenerational memory. And it takes its cue from the Akan concept of Sankofa—to look back in order to move forward.

As curator Chantel Akworkor Thompson reflects, “Personally, centring African women’s voices in this exhibition is deeply rooted in my own Akan maternal lineage... That history taught me that what’s often called ‘feminism’ today wasn’t a Western reaction, but a foundational, organizing principle in many African societies—non-binary, relational, and embedded in everyday life.”

For Thompson, this work is both personal and political. “Professionally, this inheritance pushed me to question whose knowledges are centred in exhibitions and to resist extractive approaches in favour of spaces shaped by dialogue and respect.” That curatorial stance comes through powerfully in a show where storytelling, healing, and memory take precedence over spectacle.

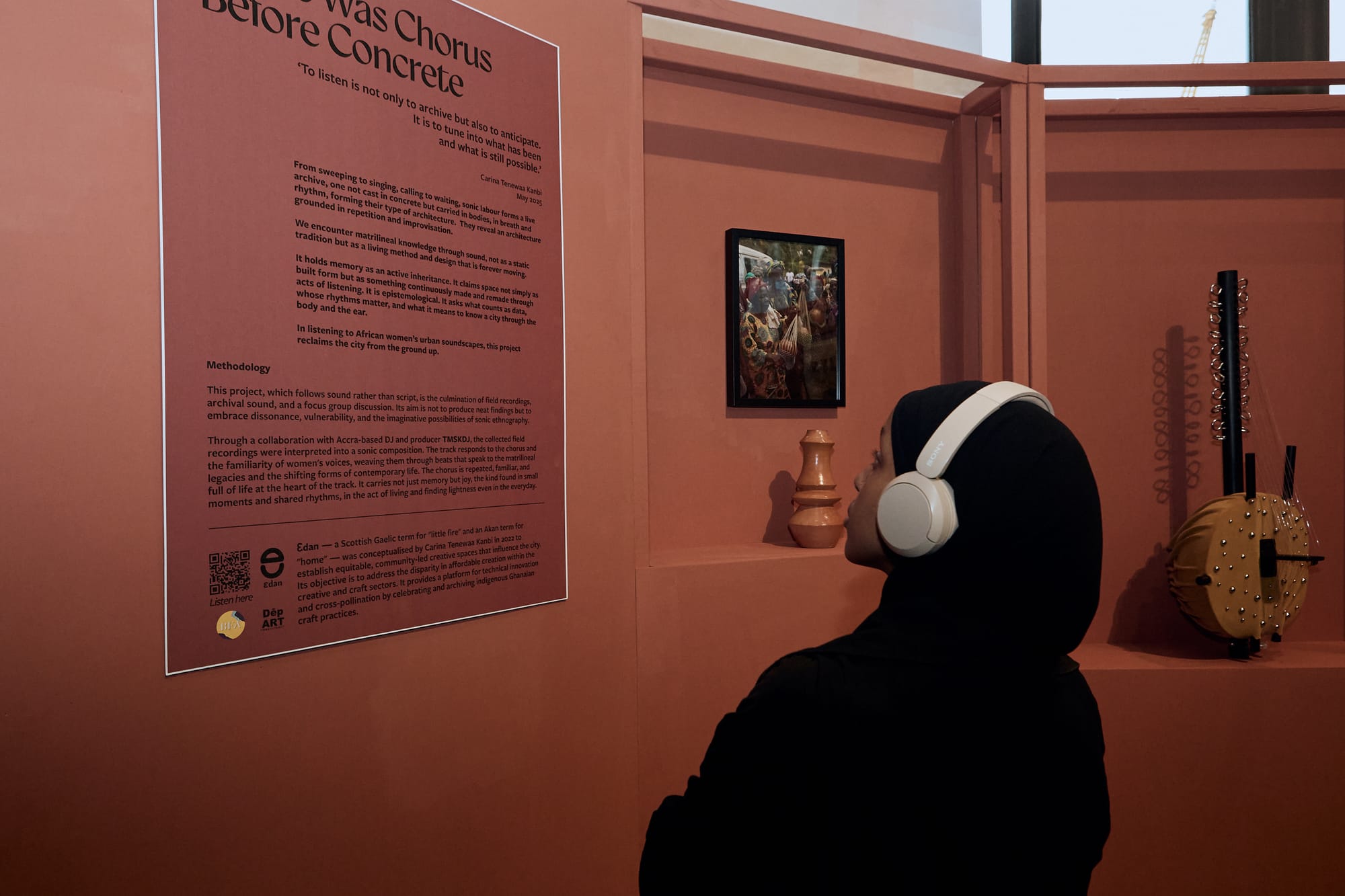

Sonic Labour as Spatial Design

At the centre of the exhibition is a powerful sonic installation titled There Was a Chorus Before Concrete, produced by Ghana-based creative lab Ɛdan in collaboration with acclaimed DJ and sound artist TMSKDJ. The piece weaves together field recordings from Sierra Leone and Ghana—songs, conversations, sweeping, waiting—into an ambient archive of women’s sonic labour.

Led by Ɛdan’s founder, Carina Tenewaa Kanbi, the research captured sound as a living architecture: something carried in the body, in breath, in repetition. “My work treats everyday sounds—like sweeping footsteps, street calls, queuing rhythms—as more than ambient noise; they are carriers of ancestral memory and agents of spatial creation,” Kanbi shares. “These sounds frame how we experience and inhabit space… Sonic labour affirms that architecture is as much about lived time and repeated gestures as it is about solid structures.”

This installation reframes space not as static but rhythmic. Not just what we build, but what we pass down. Listening becomes a practice of care: a way to design with sensitivity, memory, and imagination. TMSKDJ’s soundscape adds layers of tempo and texture, transforming domestic rituals into spatial scores. “I believe sound accesses memory in a way visuals can’t because it bypasses logic,” she explains. “It hits you in the most random way. You can close your eyes and still be transported, smell the air, feel the humidity, hear the soul of a place. It’s like a shortcut to emotion and memory.”

Here, architecture is no longer defined by form alone but by frequency. By vibration. By the affective textures of Black womanhood. As TMSKDJ puts it, “Sound doesn’t just accompany the story, it is the story.”

The Invisible Architects of Everyday Life

The exhibition also features a series of intimate, observational films by Liberian-Ghanaian filmmaker Cianeh A. Kpukuyou. These cinematic portraits capture the gestures, labours, and intimacies of women whose spatial influence is often unacknowledged. From folding laundry to preparing food, these quiet acts are revealed as the infrastructure of care, evidence of the invisible architectures women build every day.

As Thompson notes, “I wanted the exhibition to honour not just contemporary African women’s practices but also the deep intergenerational links that sustain them, even across colonial and diasporic disruptions… Here, architecture isn’t only about built forms but also social repair, storytelling, ecological balance, and community autonomy.”

By making the overlooked visible and the unheard audible, this exhibition disrupts the canon of architecture and offers a powerful counter-archive shaped by memory, feeling, and matrilineal transmission.

An Invitation to Listen, Not Just Look

Rather than present a fixed vision of architecture, Earth, Memory and the Spaces We Inhabit opens a space for feeling, remembering, and imagining. It reminds us that before blueprints, there were songs. Before foundations, there were footsteps. Before buildings, there were bodies carrying knowledge across generations.

In this space, architecture is no longer only about permanence; it’s about presence. It’s about the frequencies we inherit and the futures we tune into.

And as we step into these sculptural spaces, as we hear women’s voices ripple through the walls, we are asked to consider:

What kind of world could we design if we began by listening?

Follow the work of Black Females in Architecture and Ɛdan as they will soon be announcing a follow-up exhibition on West African soil for later this year.

Images courtesy of NOW Gallery_Alberto Romano and Shobo Photography

Member discussion