There’s something about traditional African music that refuses to die, and rightfully so. Rooted in ritual, storytelling, and spiritual expression, it flows through the veins of the continent’s past, present and future. It's in the talking drum at festivals, the ululation during weddings, and the call-and-response of a people who’ve always found joy and power in rhythm.

Fast forward a few centuries and what do you get? Afrobeats. A genre that’s not only a chart-topping global export but a living, breathing evolution of the traditional sounds that raised it. But even beyond Afrobeats, African rhythms are everywhere. Amapiano is lighting up clubs in Berlin and Brooklyn, and hip-hop producers are digging through old African samples. Clearly, the influence of traditional African music is not just being preserved, it’s being reimagined.

The Legacy of Traditional African Music

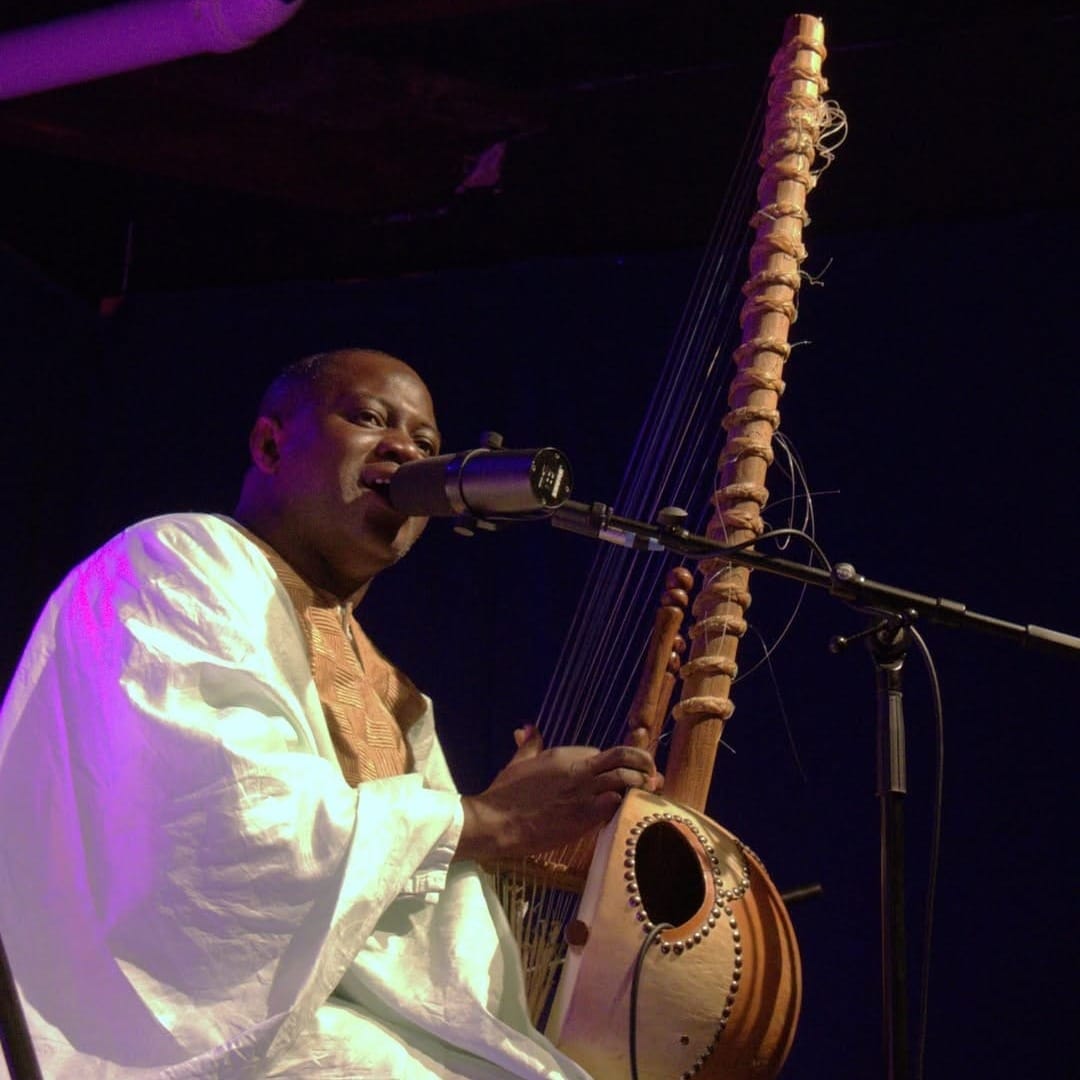

Long before global playlists started obsessively shuffling Afrobeats and Amapiano, music in Africa wasn’t just entertainment, it was everything. It was how entire communities remembered, rebelled, worshipped, and healed. From the griots of Mali, whose kora melodies carried the oral history of empires, to the Yoruba bata drums that summoned deities during sacred rituals and festivals, music was, and still is, a living archive of African identity.

Every single region had its rhythm. In East Africa, taarab blended Swahili poetry perfectly with Arabic and Indian instrumentation. In Central Africa, soukous music emerged from Congolese rumba, which is itself a descendant of Afro-Cuban music. West Africa gave us Highlife, Fuji, Apala, and Agidigbo; each tied to communal gatherings, spiritual ceremonies, royal courts, and everyday survival.

And these weren’t just passive sounds. They moved bodies, yes, but they also told stories, preserved dialects, called ancestors, and shouted protest. Music was woven into the social fabric of the society itself: births had songs, funerals had chants, and even farming came with its own “soundtrack.” The instruments, such as balafons, talking drums, mbiras, and ngomas, weren’t just tools of sound. They were extensions of the African soul.

Even though it may be easy to think these traditional sounds and layered heritage have faded with time, they haven't. Rather than become relics of the past, they’ve evolved, reshaped by colonization, modernity, and the diaspora, and now they've found new life in today’s genre-defying African sound.

Afrobeats: A New Chapter

Today’s Afrobeats (not to be confused with Fela’s singular “Afrobeat”) carries within it layers of Yoruba percussion, Highlife melodies, Igbo call-and-response, and Hausa rhythms, all rolled into one sound. And these traditional roots are the soil from which global stars like Wizkid, Burna Boy, Ayra Starr and Asake continue to grow.

Take The Cavemen, for instance. This Nigerian duo is Highlife reincarnated in Gen Z form. Their music is soaked in ancestral melodies, sung mostly in Igbo, and backed by guitar licks that wouldn’t sound out of place in a 1970s Enugu bar. And yet, they tour both Lagos and London, pulling in fans who don't even speak the language.

Also, Burna Boy’s “Twice As Tall” and “African Giant” albums are practically thesis papers in African music lineage. You can hear everything from Fela to Angelique Kidjo to South African Zulu choirs in the production.

Rema, Afrobeats’ (or Afrorave, as he calls it) experimental poster boy, has also openly cited traditional Nigerian genres like Fuji and church music as his early inspirations. His voice dips into melodious chants, and his beats often merge trap drums with bata drums. On hit song, “Charm,” he blended pop with traditional cadence.

On another fan favourite, “Is it A Crime”, he sampled Sade, a British-Nigerian icon whose own music is steeped in African jazz. Even in his latest work, Rema’s art feels like a cultural puzzle, part Benin kingdom royalty, part Lagos club night, part SoundCloud era. And so far it seems to be working for him.

Amapiano: From Township to TikTok

Over in South Africa, Amapiano is having its own moment, and it’s not a moment that’s ending anytime soon. With its log drums, upbeat chords, and slowed-down house beats, Amapiano draws directly from kwaito, which itself evolved from marabi and traditional South African styles like maskandi and mbaqanga. Today's SA artists like Kabza De Small, Uncle Waffles, and Musa Keys are spreading a gospel that feels both new and deeply ancestral.

In Ghana, acts like King Ayisoba fuse traditional two-string kologo sounds with modern electronics. His music feels raw, almost ceremonial, yet it fits in perfectly at global festivals. Wiyaala blends tribal chants with pop melodies and sings in local languages like Sissala and Waale.

Amaarae, one of Ghana's most well known exports mixes different styles in her music, combining Afrobeat with modern, futuristic sounds. Her unique voice and bold style have made her popular around the world and one of the most exciting artists from Ghana today.

In Kenya, Sauti Sol’s rich harmonies carry the soul of Benga and Taarab music, while still collaborating with global acts like Burna Boy and Patoranking. And Tanzanian artists like Diamond Platnumz and Zuchu incorporate elements of Taarab and traditional Swahili rhythms into their Bongo Flava sounds, finding new ways to modernize them for a younger, more pop-hungry audience.

Global Artists with African Roots

Unsurprisingly, even the diaspora isn’t left out either. British-Gambian artist J Hus combines Afro-infused beats with his grime flows and rap, often referencing juju and traditional lore in his lyrics. And French-Malian star Aya Nakamura writes pop bangers with Afro-Caribbean and West African inspiration, proudly giving Francophone African teens a soundtrack that sounds like them.

Even American R&B and pop have started to bend toward African rhythms. Tems' soulful, almost spiritual vocal style owes as much to old Yoruba hymns as it does to alternative R&B. And with her writing credit on WizKid’s “Essence” and major feature on “Wait for U,” she’s exporting not just her voice, but an entire emotional sound rooted in African music.

And it’s not just African artists who are paying homage. Whether consciously or not, Western musicians are also tapping into traditional African archives too.

On “IGOR,” Tyler the Creator sampled a song by Zimbabwe’s Hallelujah Chicken Run Band, a 1970s outfit that merged Shona traditional music with funk and electric guitars.

Drake’s “One Dance,” arguably the song that opened the door for Afrobeats on global charts, featured Nigerian singer Wizkid and borrowed from the rhythm of UK Funky and Afro-house, which are both descendants of African drumming and polyrhythms.

Even Beyoncé’s “The Lion King: The Gift” wasn't just a guestlist of Afrobeats features. It was a cultural mixtape, with traditional chants, Swahili interludes, Yoruba proverbs, and even ancestral drums all layered into the sound design. It was a full-on immersion into traditional Africa.

Conclusion

What we’re seeing today isn’t just a comeback of African music, it’s a reshaping of the global sound as we know it. Not long ago, this kind of music was seen as old-fashioned or not cool enough. But now, traditional African music isn’t being ignored anymore; it’s taking the lead, with its drums, chants, and deeply cultural roots.

Member discussion