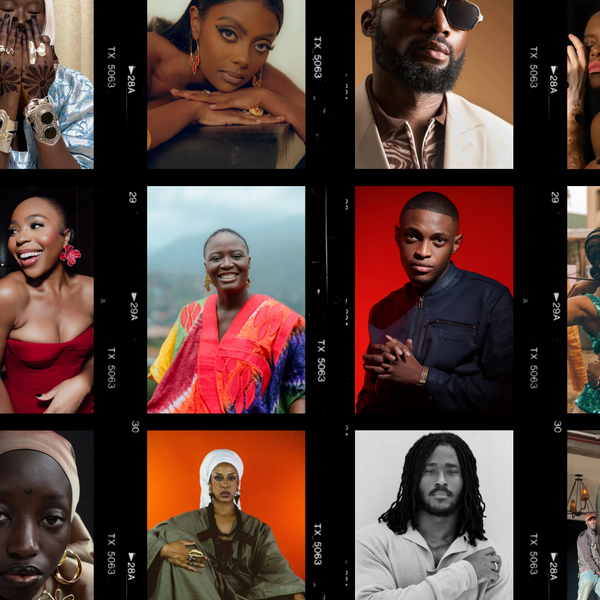

Marième Mboup, known artistically as Yumboë, is forging a path in fashion that refuses to follow trends or conform to industry expectations. Born and raised in Dakar, Senegal, and now based in Montreal, Marième is a stylist, textile exploration artist and visual storyteller whose work is rooted in heritage, identity, and community. She describes her practice as an ongoing exploration, creating looks and garments that push the limits while staying deeply anchored in the rhythms of Senegalese culture.

In this conversation, we spoke to the multidisciplinary creative about how she made the leap from modelling to styling, the pressure of overproduction in the fashion industry, and why she’s choosing to slow down in pursuit of intention and truth. We talked about the ways her community, both inherited and chosen, remains central to her work and her hope for more accountability in a fashion industry that has long borrowed from African cultures without recognition.

If you're curious about how fashion can be a tool for storytelling, resistance, and cultural preservation, or you just want to hear from someone who’s doing it with honesty and heart, keep reading. Marième is building something special, and it’s only the beginning.

Just to understand a little more about who you are, how did your childhood and background influence your creative work in any way?

So I grew up in Dakar, Senegal. I was born and raised there until I was 18. When I think about how my childhood influenced my creative work, I’d say it’s less about how I was raised or who I was as a child, because honestly, I’ve changed a lot, and more about the culture I was surrounded by. My cultural heritage has had a huge impact, especially when it comes to clothing and textiles. I’ve always had examples around me of the elegant Senegalese woman; the way she accessorises, the gold jewellery, these images really stuck with me. And that’s why gold is such a key part of how I present myself and my work today.

I think that influence really became clear once I moved away. When you leave your country, you start to see how much your culture has shaped your personality and your interests.When I came to Canada, I found myself wanting to reconnect with that part of me, especially as I started getting deeper into fashion and exploring textiles. Growing up at home gave me this foundation that continues to show up in the way I dress, how I present myself, and even what I choose to highlight in my work or on social media.

So overall, my cultural heritage and the fact that I grew up back home continue to shape the direction of my creative work and the way I express myself.

That makes a lot of sense, and it really shines through. You once described your style and creative exploration as atypical, not quite what people expect when they think “into fashion.”What does that word mean to you now? And how has that idea evolved or influenced your journey over time?

Atypical—I think for me, that word has always meant something outside the norm, outside the conservative idea of what’s considered normal. It’s something unexpected, unfamiliar, or striking to the eye. That definition hasn’t really changed for me over time.

What has evolved, though, is how I see it show up in my art. Anything can be atypical: a personality, a look, an accessory. It’s just something different, something you don’t see often. Now that I’m more immersed in fashion and paying attention to detail, I’m more aware of what’s considered "typical" and what isn’t.

For example, when it comes to transgressive garments or fashion that challenges conventions, I’ve become more educated on those nuances. But I’ve also realised that "atypical" is really subjective. When you’re growing up at home, in your culture, nothing feels atypical; it just feels normal. It’s only when you leave and experience other cultures that you realise the way you dress, or the way you express yourself, might be seen as different or even radical.

Like, when I wear my boubou or traditional accessories, it’s normal to me, it’s my culture. But here, people might see it and say, “Wow, that’s maximalist!” It’s taught me how perception changes based on environment. What feels natural and familiar to me can feel extraordinary or unconventional to someone else.

So yeah, that’s kind of my relationship with the word atypical.

Especially now with the internet and media exposure. What’s considered traditional or everyday in one place can take on a whole new meaning somewhere else. You use pins as a specific creative tool you enjoy. Are there any other tools in your styling or draping toolkit that you swear by, like absolute must-haves?

Aside from pins and fabric… let me think. Honestly, it’s mostly just that—pins and fabric. Draping really only requires those two. You need the fabric and something to pin it onto, whether that’s a mannequin or a human body.

It also depends on the kind of styling I’m doing. If it’s a straightforward draping project, that’s all I need. But if it’s a more layered styling contract where I’m incorporating other garments, then I’ll bring in other pieces, maybe some double-sided tape, especially if something needs to hold a specific shape or stay put. But if someone told me I had a draping set tomorrow, I’d literally just show up with my fabric and pins plus accessories, maybe, depending on the brief.

I love that. My next question takes us back to something you mentioned earlier, the women in your life introducing you to fashion. How would you say your family, your friends, and your community have shaped your creative lens?

They’ve shaped pretty much all of it. The women in my life are my biggest inspirations, not just my family, but my friends too. I’ve had the chance to meet incredibly creative and genuine people since moving here, and they inspire me every day, both in fashion and in how I choose to exist as a person.

My sister, for instance, is my older sister, and as the eldest girl in the family, she naturally took on a kind of motherly role. Especially when I moved here, because she had come before me. She was the one who introduced me to modelling. My first shoot was with one of her close friends, a really talented photographer, and she encouraged me to go for it. That was the beginning.

She’s always guided me, especially when I felt lost, like when you're in a space where you're not even studying something you love. She's always been a steady hand and a big inspiration.

Then there’s my mom. I think I really began to appreciate her style and influence after I moved away and started exploring fashion for myself. Growing up, our styles were nothing alike; my style five years ago is unrecognisable compared to now. But through her, I started rediscovering myself as an adult, reconnecting with my culture, and learning to express it through what I wear, how I dress, how I accessorise, and how I carry myself. The women in my life have played a huge role in shaping the way I think and create today.

That’s beautiful. I also wanted to ask about community more broadly. I’ve noticed it’s a recurring theme in your yearbook project, in your styling work, and even in your visual storytelling. What does community mean to you? And how does it tie into the way you tell stories, especially stories about identity or shared experiences?

Community, to me, is everything. I honestly can’t imagine my life without it. Back home in Senegal, for example, we’re extremely community-driven, more than anywhere else I’ve seen. It’s something we’re known for, and I grew up with that deep sense of connection all my life.

So when I moved to Canada, I didn’t feel like I had completely lost that because I still had people I knew here, and there's also a sizable Senegalese community. But at the same time, I quickly realised how different things are here; Canada is much more individualistic. That was a big shift for me.

I had to find, or rather build, an additional community, especially in the creative space. Even though there are many Senegalese people here, I didn’t have that many close friends from back home in the same space. So I had to carve out a new community, one rooted in creativity.

What really worked for me was connecting with people who were not only around my age but were also immigrants. We shared similar creative interests and also similar lived experiences. That made it easier to relate emotionally, creatively, and culturally.

Even though I resonate with many BIPOC communities here too, the group that really gave me a sense of safety and belonging was the creative immigrant community in Montreal. And I’m grateful we found each other.

That community has played a huge role in my creative journey and growth. Collaborating with others has been central to how I’ve evolved as an artist. Montreal is very open in that sense, sometimes even too open, but it means people are always down to create together, to learn, and to support. That openness helped me a lot. It gave me space to shape myself as an artist and as a person.

I love that you were able to find your community and even discover new parts of yourself in the process. Speaking of your projects, I’m curious, how do you choose the ones you take on? And what kinds of stories are you most compelled to tell through your art and your garments?

The stories I’m most drawn to are the ones with meaning and purpose. Whenever I choose a project, the first thing I need to do is meet the person behind it. That conversation is crucial. What’s the intention? What are you trying to represent? Because if we don’t share the same vision, the collaboration won’t work. The outcome won’t feel true, and it won’t represent the story the way it’s meant to be told.

For me, it’s about alignment, both with the person and the story. Where is this story coming from? Is it personal? Is it from your community? The more connected you are to a story, the more powerful the impact. And for me to do my best work, the story has to resonate. If I can’t relate to it, I can still work on it, but the passion won’t be there. The work won’t be as honest.

So I always make sure we share a common vision, and that the story matters to all of us involved. I’m usually drawn to BIPOC, African, Afro-descendant, Caribbean, or Indigenous narratives. Most of my projects are rooted in African cultural heritage, mythology, or history. I once worked on a project about Indigenous and Black cowboys in the American West. I gravitate toward stories that involve deep research, stories that teach me something. If I’m not learning, I’m not growing.

I need to walk away from every project having grown in some way. What new knowledge did I gain? What history was unfamiliar to me? What can I research to better understand the context? That’s really how I decide who and what to work with.

So, it sounds like for you, art and fashion are tools for cultural preservation and, in many ways, a form of resistance. I want to dig deeper into that. In what ways do you think fashion contributes to preserving culture? Do you think it plays a vital role? Because especially in media, we often say we're "telling stories" or "educating people," but do you think fashion genuinely helps preserve and communicate culture?

I think it really depends on the situation; it's a case-by-case thing.

Take Canada, for example. It’s a Western country, but when it comes to fashion spaces, I do think we have the opportunity to represent and preserve our culture in certain ways. That said, there’s always the risk of appropriation. Because our cultures are beautiful and visually striking, people may want to include them in their projects without fully understanding what they’re drawing from. And that’s where it can slip into appropriation, when it becomes just a trend or an aesthetic, rather than a true representation of something deeply rooted.

It’s not just about visual appeal. These things carry meaning. They’re part of our history, our values, our whole culture. So again, it really depends.

Fashion spaces and creative projects can absolutely serve as a means to preserve culture. I believe that any project that accurately and respectfully represents your cultural heritage contributes to its preservation. It doesn’t matter if it’s modern or traditional as long as it's done with intention and respect.

But here’s why I say it’s case by case: Let’s say you’re working on a project where the creative director wants to draw from Senegalese mythology or cultural stories. If that person isn't Senegalese, or isn’t Black or of African descent, it raises questions. Why do they want to explore this? Do they actually know what they're referencing? Have they done their research? Or are they just using it because it looks cool or trendy?

That’s where intention becomes so important. What are they going to do with this culture? Are they going to westernise it? Are they going to strip it of its meaning?

So yes, fashion spaces can be powerful tools for cultural preservation, especially for West Africans and BIPOC communities in general. But we need to be careful about who we collaborate with and make sure the intent is respectful and informed.

Thank you for sharing that. I completely agree; it often comes down to intention, and really learning the meaning behind what’s being represented. One other question I had was around the challenges you’ve faced as you’ve grown and evolved in the industry, and how you’ve been able to subvert or navigate those challenges.

In the fashion industry itself… I'd say I’ve faced more challenges as a model than as someone working in fashion design or textiles. As a dark-skinned model, you always run into issues; there's always going to be a shoot where they don't have your shade of foundation or they mishandle your hair. So yeah, modelling has definitely come with its own set of challenges.

The way I’ve dealt with that is by being honest and open, speaking up about those insecurities and calling out what’s not okay. I think if you want to be part of an industry like fashion, you need to be able to stand your ground, because situations like that will happen.

But when it comes to textiles, styling, and just exploring fashion more broadly, my biggest challenge has been learning how to overcome over-creation. What I mean is, especially in Montreal, there’s this pressure to constantly produce. Every week, there’s a new shoot, a new idea, something happening. People treat it like it’s normal, but it’s not. And when I first started, I really bought into that. I thought, “Whoa, I’m not doing enough, I need to catch up.”

So I took on a lot of projects that I did enjoy at the time, but looking back, me now, in 2025, I don't really relate to those works anymore. And that’s okay. They helped me grow. They taught me things. But the real lesson was learning to slow down. I had to resist the pressure of what everyone else was doing and stop letting social media set the pace for me.

I had to learn to take time not necessarily to perfect, but to develop my craft. To make sure whatever I was creating came with intention, came with research. That’s what I needed.

That really struck a chord with me. I don't think a lot of people talk about over-creation enough. I remember having to pause my Instagram for a while because every time I opened the app, someone was doing something amazing, and I’d think, “I need to be making something too.” But like you said, especially for people who love learning and research, it just takes time. And that’s okay. Some people spend two years on a single project, and that’s still valid. But social media makes it feel like we need to keep producing at a ridiculous pace. So, thank you for bringing that up; it’s such a real challenge.

As you continue evolving as an artist and a stylist, what are some of your dreams or visions for the industry at large and for yourself?

For the industry at large, I think my vision is for Afro-descendant creators to receive more credit. I strongly believe that many elements of today’s Western fashion industry have been heavily influenced by African traditional garments, long before fashion was even considered an “industry” on the continent.

We've contributed so much through our garments, our patterns, the ways we construct and wear clothes, and the meaning we attach to different looks. Our influence is undeniable. My hope for the future is that the African cultures that inspire so much of Western fashion not only receive proper credit but are also given space within the industry, at fashion weeks, in exhibitions, and on global fashion stages. Because honestly, 60% of what’s in those spaces came from us.

So yes, my vision is about recognition, representation, and also accountability especially from Western designers and brands. They often draw from African aesthetics without acknowledging their sources. They'll claim it as their own or label it as vague "inspiration," but if you trace certain patterns seen in brands like Louis Vuitton or Gucci, you’ll find them in West Africa, Central Africa, embedded in textiles made by artisans long before those fashion houses even existed. It’s not a coincidence. I hope that in the future, there’s more transparency and accountability from these brands.

As for my personal journey, I’m still finding my way in the fashion industry. I know I want to continue learning, refining my technique, and becoming more specialised in design and fashion history. I want to be able to tell stories and histories through my garments. Where it all leads, I leave that in God’s hands.

But what’s most important to me is not losing the passion. I want to pursue paths that keep me grounded and inspired, never creating for clout or just for money. That’s not why I fell in love with textiles and design in the first place.

Thank you so much for sharing that, especially on the topic of accountability. I completely agree. Even within African fashion, there’s still a lack of proper credit; brands here, too often fail to acknowledge the artisans behind their work or the true sources of their inspiration. It’s a wider issue that affects both local and international scenes.

And regarding your journey, I think your approach to keep exploring and staying rooted in your passion is such a beautiful way to move through this industry. Those are all the questions I have. Thank you so, so much. This has been great.

Member discussion