Long before Netflix or even printed books, people would gather around fires under starlit African skies to hear stories. Not just any stories; these tales were passed down through generations, with each telling preserving history, teaching morals, and connecting communities to something larger than themselves.

What's incredible is how these ancient myths and beings haven't just survived, they've thrived, showing up in modern films, music, literature, and even Marvel comics. And they continue to captivate and influence our world today.

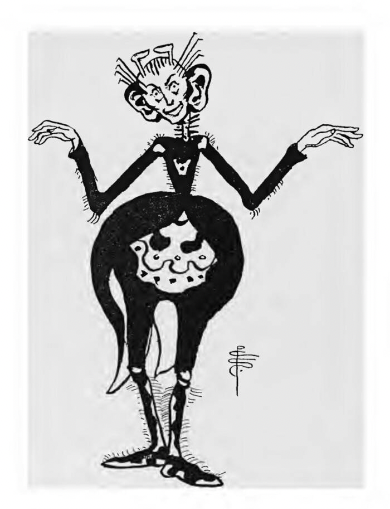

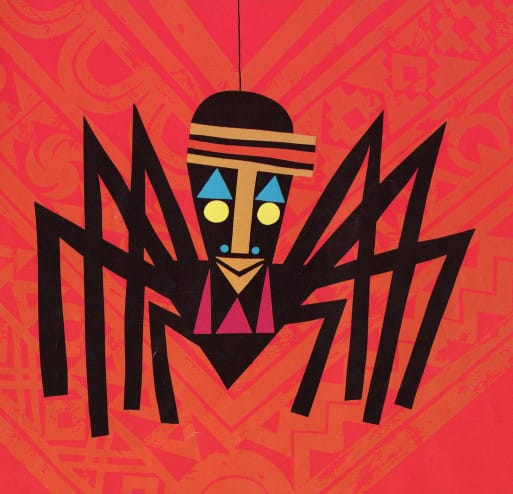

Anansi The Spider

Origin: Ghana (Akan people)

If you think Spider-Man is cool, this is his even cooler ancestor. Anansi (or Ananse) is a trickster god who appears as a spider and outsmarts bigger, stronger opponents with nothing but his wit. According to legend, he's the spirit of all stories, and he owns every tale in the world.

What makes Anansi special is that he's not perfect. He's greedy, selfish, and manipulative, but also clever and resourceful. He reflects real human nature, flaws and all.

In 2003, Marvel Comics revealed that Kwaku Anansi was the first Spider-Man in their multiverse. He also appears as a character in Neil Gaiman's 2017 American Gods TV series and got his own novel, Anansi Boys.

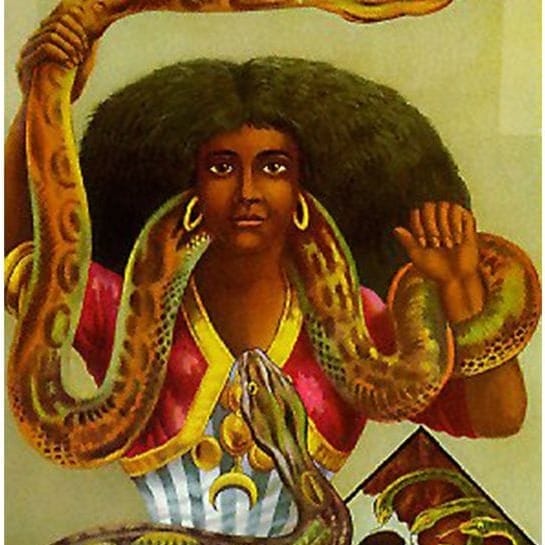

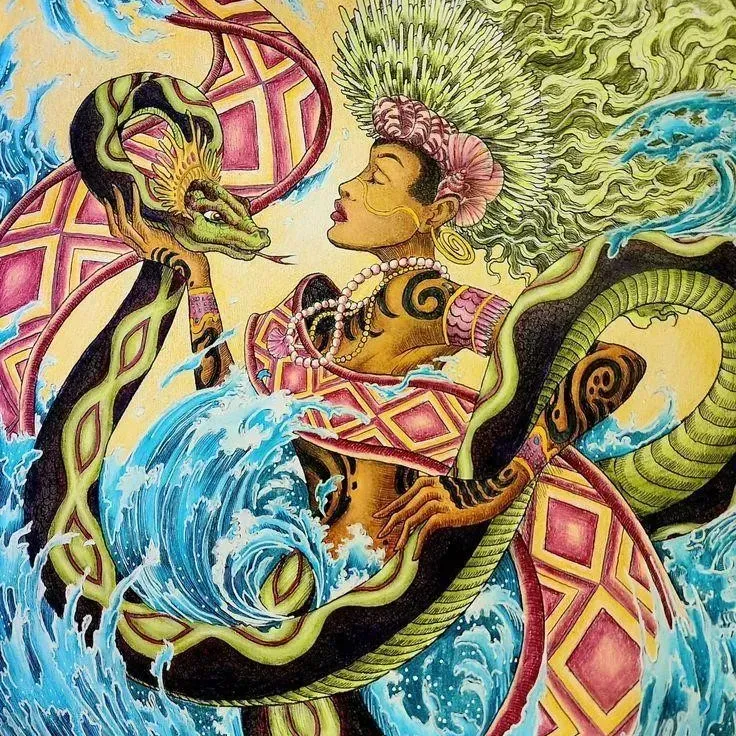

Mami Wata

Origin: West and Central Africa (especially Nigeria, Cameroon, Congo)

Mami Wata, whose name comes from pidgin English for "Mother Water,” is a fierce water spirit. If you worship her properly, she'll bless you with wealth and good fortune, but cross her, and you might end up drowning or going mad.

Her appearance is as fluid as water. Sometimes she has a fish tail, sometimes snakes wrapped around her body, sometimes she's just a beautiful woman with long flowing hair. Her origins blend African water spirit traditions with European mermaid images from trading ships in the 15th century.

Unlike many mythological beings, Mami Wata worship is alive and growing, and she's central to modern Vodun practices across West Africa and the diaspora. In 2008, UCLA's Fowler Museum hosted a major exhibition showcasing five centuries of Mami Wata art. She's even become a character in the West African film industry.

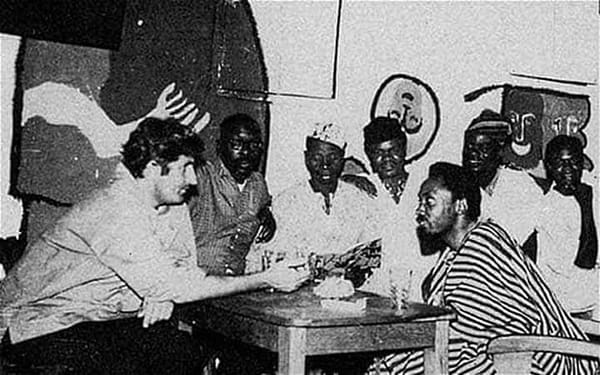

The Epic of Sundiata

Origin: Mali Empire, 13th century (Mandinka people)

This is Africa's greatest hero's journey, told by griots for over 700 years. Sundiata Keita, also known as the “Lion Prince,” was a real historical figure who founded the Mali Empire, but his legend has grown into something extraordinary.

Despite a prophecy claiming he would be a great ruler, he was born unable to walk and faced constant bullying from his jealous stepmother. But when he finally stood up, in response to his mother's tears, he became a legendary warrior who defeated the evil sorcerer-king Soumaoro Kanté and established the Mali Empire.

Today, the myth is much more than just a history lesson, it is a foundational part of West African identity. It’s a classic "Lion King" story that shows how Sundiata’s leadership turned a divided region into one of the wealthiest and most influential empires in the world.

Nyami Nyami

Origin: Zimbabwe and Zambia (Tonga people)

Picture a massive serpent with the head of a fish or dragon, dwelling in the Zambezi River. This is Nyami Nyami, the protector of the Tonga people. It’s also known as the Zambezi Snake Spirit or Zambezi River God.

The myth starts in the 1950s when colonial governments decided to build the Kariba Dam. The Tonga people warned that Nyami Nyami would never allow it as the dam would separate him from his wife upstream. Then came the floods. In 1957, the worst floods ever recorded washed away much of the partly built dam, killing workers. The next year brought even worse floods. The dam was eventually completed, but many believe Nyami Nyami still tries to reach his wife with every earthquake.

Nyami Nyami has become a powerful symbol for environmental conservation and indigenous rights, and the Nyaminyami Festival celebrates him each September.

The Yoruba Myth of Creation

Origin: Nigeria (Yoruba People)

In the beginning, there was only sky and water. The supreme god Olorun sent Obatala, one of the Orishas, to create solid land. Obatala climbed down from heaven on a golden chain carrying sand, a hen, and a palm nut. When the chain ended midair, he poured the sand onto the waters, and the hen scattered it, forming the first land at Ile-Ife, the sacred birthplace of humanity.

In some versions, Obatala later created humans while drunk on palm wine, making some with disabilities, hence why he became their divine protector. Other Orishas followed to shape the world: Ogun brought iron, Shango thunder and justice, Oshun love and rivers, and Yemoja the waters.

The Yoruba pantheon is one of the most widely believed myths in the world, and millions of people across Africa, the Caribbean, and the Americas still worship these Orishas today. In contemporary culture, the Orishas appear in music, literature, visual art, film and television.

Legendary African Music Dynasties That Shaped Sound Across Generations

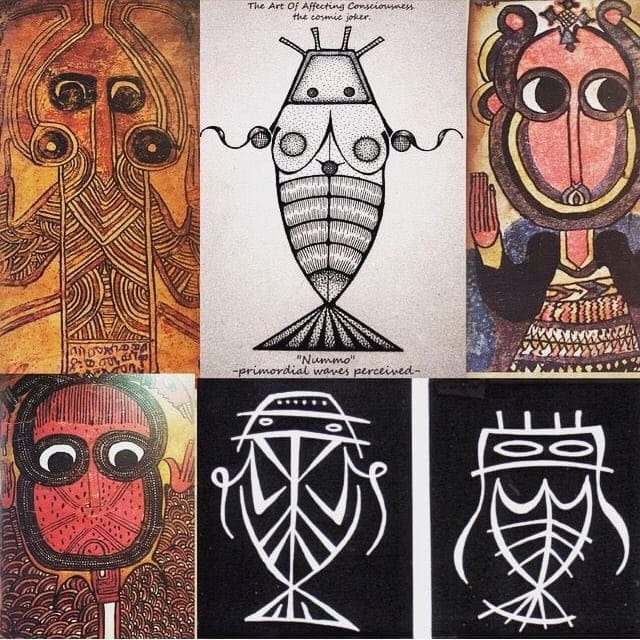

The Nommo

Origin: Mali (Dogon people)

The Nommo are amphibious, fish-like beings with humanoid upper bodies. According to Dogon cosmology, they came from a world circling Sirius, the Dog Star, and were the first living creatures. They were created by the supreme god Amma and were born as pairs of twins, perfectly balanced and representing order, harmony, and the correct way of being. Water was their element, and speech was their gift.

But creation didn’t go smoothly. One twin, known as Ogo, rebelled and tried to create a world alone. His failure caused chaos and imbalance in the universe. To fix this, Amma sacrificed one of the Nommo, whose body was scattered across the cosmos. From that sacrifice came the stars, the earth, time, and life itself. The Nommo were then reborn, multiplied, and sent to earth.

When the Nommo descended, they arrived in an ark accompanied by thunder, fire, and rain. They taught humans language, agriculture, law, and spiritual knowledge. Because of this, the Dogon believe that speech itself is sacred, carrying the life-force of the Nommo. Today, they remain central to Dogon rituals, masks, and art.

Yumboes

Origin: Senegal and Gambia (Wolof and Lebou people)

Not all African spirits are terrifying. The Yumboes are pearly-white, two-foot-tall beings with silver hair who live beneath hills. They're West Africa's equivalent of European fairies and are mischievous, magical, and enjoy late-night dancing.

They come out at night to feast on stolen corn and fish, sometimes inviting humans to their moonlight celebrations. They're also gentler spirits who don't typically harm humans unless provoked.

The Aziza

Origin: Benin (Fon and Ewe people)

Deep in Benin's forests live the Aziza. They’re small, hairy, fairy-like creatures that dwell in anthills and silk-cotton trees. But they aren't scary spirits; the Aziza are helpers and teachers.

Hunters who show proper respect to the forest might encounter an Aziza, who provide magical assistance or teach spiritual knowledge. They supposedly shared practical wisdom: which plants heal, how to use fire, and agricultural techniques.

The Aziza myth represents the Benin belief that the forest isn't just a resource to exploit, but a living space inhabited by beings who can be allies if treated with respect.

Mamba Muntu

Origin: Democratic Republic of Congo and Republic of Congo (Bantu groups)

Mamba Muntu lives in Central Africa's great rivers. She’s similar to Mami Wata, but is distinct to the Congo region. She's also been described as a mermaid, crocodile, or snake. The name means "Mother of People."

On sunny days you might spot her sitting on rocks, combing her long hair. If you're able to get some of her hair or comb, she'll visit you in dreams to share prophecies or grant wishes, but at a price.

In the Congo Basin, where rivers are highways, food sources, and spiritual centres, Mamba Muntu represents the relationship between communities and waterways.

The Tokoloshe

Origin: South Africa

The Tokoloshe (also spelled Tokoloshi) is one of Africa's more terrifying myths. It's a mischievous, and sometimes dangerous spirit from Zulu and Xhosa mythology in Southern Africa. It’s often described as small, hairy, and humanoid, and believed to be summoned by witches to cause trouble: breaking things, bringing illness, stealing, or attacking people while they sleep.

The Tokoloshe typically feeds off of fear and secrecy. To protect themselves, some people traditionally raise their beds on bricks so it can’t reach them at night. In many stories, it’s invisible to adults but visible to children and those with a high spiritual sensitivity.

The Tokoloshe was one way communities explained misfortune, fear, and the unseen forces of life. Today, it lives on in pop culture, street slang, art, and horror stories, proof that folklore doesn’t disappear, it adapts.

Conclusion

These stories survived because they're fundamentally human. Anansi's clever trickery speaks to anyone who's ever been underestimated. Sundiata's journey from disability to greatness inspires everyone facing adversity. Nyami Nyami's resistance reminds us that development can come at a cost. But beyond their individual lessons, these myths collectively preserve something invaluable: African voices telling African stories.

This National Storytelling Week, the greatest lesson is this: stories are living things that breathe, change, and grow with each telling. The same tales that entertained our ancestors now entertain us, and will continue entertaining future generations in ways we can't even imagine.

Member discussion