Ozoz Sokoh is many things: a culinary anthropologist, writer, educator, and self-proclaimed food explorer. But above all, she’s a storyteller, one who tells the story of Nigeria through its food.

Known to many by her online moniker Kitchen Butterfly, Ozoz has spent over a decade tracing the roots, rituals, and richness of Nigerian cuisine. What began as a personal blog in 2009, born out of homesickness and a love for cooking has evolved into a vibrant archive of recipes, research, and reflections on identity, memory, and migration. With a background in geology and a scientist’s eye for detail, she’s turned her attention to what’s on our plates: asking what it says about where we come from, and how we carry that forward.

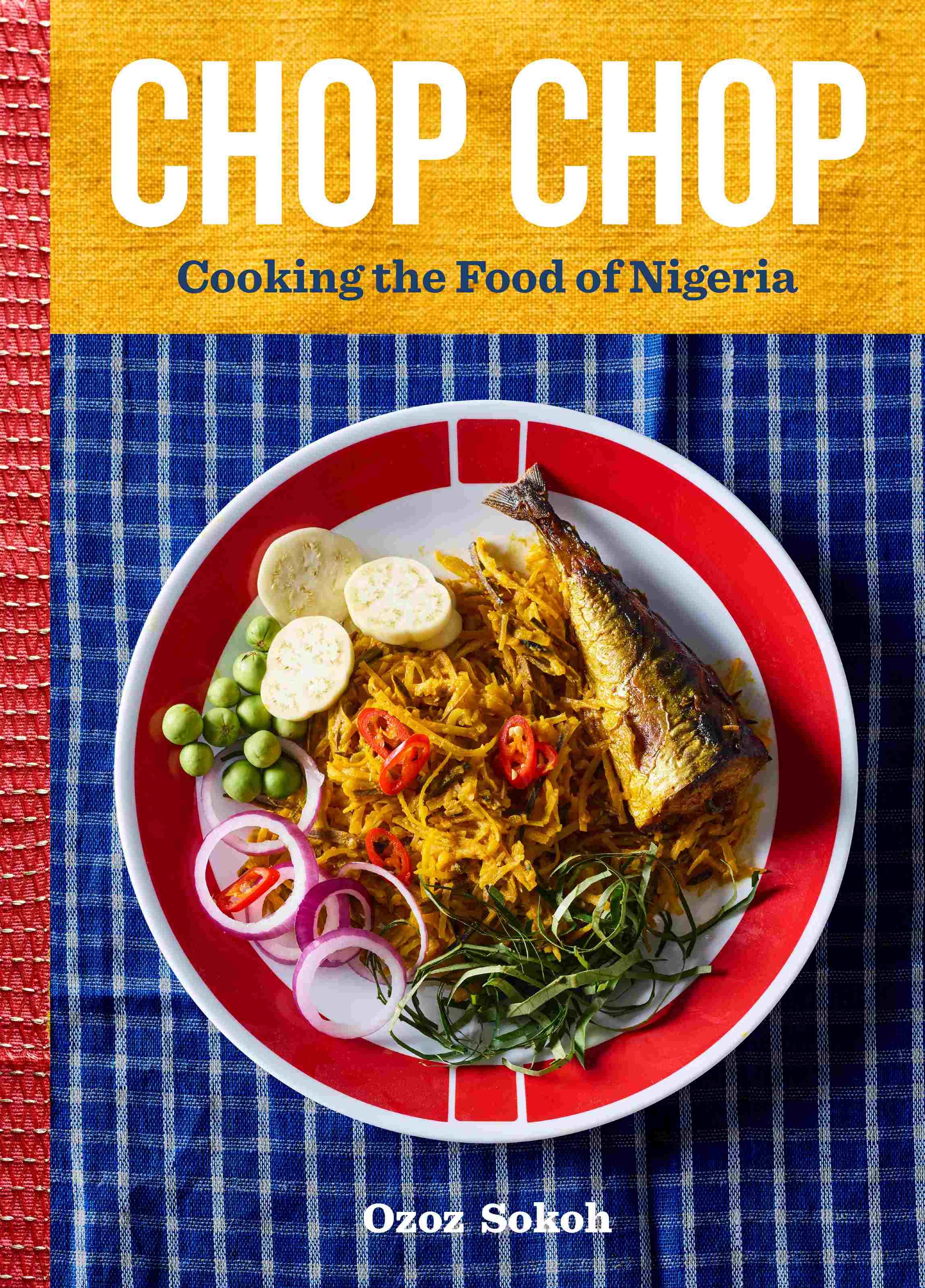

Her new cookbook, Chop Chop: Cooking the Food of Nigeria (Artisan, 2025), is a milestone for Nigerian culinary storytelling. Spanning all six regions of the country, the book offers over 100 recipes from beloved staples like jollof rice and suya, to lesser-known gems like yòyò (fried whitebait) and the spice aridan. But Chop Chop is more than a cookbook, it’s an invitation to see food as history, protest, comfort, and connection. It’s a cultural record, written for those who want to remember, rediscover, and reclaim.

In this conversation for Marmalade Collective, we spoke with Ozoz about the long journey behind Chop Chop, the complexity of documenting Nigerian food with care and nuance, and how the kitchen can be a space of resistance, healing, and cultural pride. We touched on everything from food diasporas and personal rituals, to the politics of naming and the joy of soaking garri. This one’s for the culture and the hungry.

My first question really is, I know you went abroad, first to Liverpool, to study geology, which is quite a shift from what you’re doing now. I wanted to ask: what inspired that transformation, and how has your background in science shaped the way you approach food?

So, I had actually studied at a University in Nigeria for three years before moving abroad to study geology. I chose geology because Nigeria is rich in oil and gas, and I thought, “I’ll get a good job when I graduate, and I’ll have money, simple.”

But of course, things didn’t quite work out that way. Partway through my studies, I was homesick and tired. But I knew I had no choice; my parents were paying international fees, so I had to push through.

It was during that period that I began to think about food as more than just eating. Being homesick, I realised that Nigerian food brought me comfort. So every time I felt down or missed home, I’d cook, hang out with friends, and chat. There was food, yes, but also community, sustenance, memory, and nostalgia.

I graduated as a geologist, moved back to Nigeria, got a job in the field, and later moved to the Netherlands. At that point, I had a good job and I was making money, but I wasn’t enjoying it. I realised that I didn’t want to keep doing that, but the catch was, I didn’t know yet what I wanted to do.

So I started paying attention to myself to what brought me joy, what I was naturally drawn to. I remember one Friday night: my ex-partner and a friend were writing blog posts while I was in the kitchen making Chinese fried rice. I was chopping green beans and peppers in our kitchen, and suddenly it hit me, I love food, and I’ve always loved writing. Maybe I could start a blog.

Funny enough, years before that, I had tried to convince my dad to let me study literature abroad instead of geology. He said absolutely not, that was something I could do on weekends. But my mom’s an English teacher, and I’d always written essays, poems, and compositions.

That night in the kitchen felt like a lightbulb moment. I’d been reading food blogs for a while, and it suddenly felt like the right thing to do. I started brainstorming names, first A Little Bit of Chilli, because I loved adding dry pepper and chillies to everything, even desserts. But that felt too stereotypical, given how people often associate Nigerian food with spiciness.

Then I thought of I’m Not a Plastic Spoon because I liked wooden spoons. Still, that didn’t feel quite right either.

At the time, my children were really young, three under the age of four, and we used to visit a butterfly garden often. One day, I saw all the stages of a butterfly’s life, from egg, to caterpillar, to chrysalis, to butterfly, and it struck me that it mirrored my own journey with food.

As a child, I didn’t eat much at all. Then I started eating. Later, I found comfort in food. And by the time I began writing my blog, I was starting to think about the historical and cultural context of food.

So I launched the blog while still working as a geologist. But over time, my food work began to grow. I tried everything, photography, filmmaking, food styling, anything related to food, I explored it.

I started the blog in 2009, and after nine years, in 2018, I quit my geology job, and I fully transitioned into working in food. It was a long journey, but absolutely worth it. My scientific background gave me skills that still serve me today: observational, documentation, and experimental approaches. So when I’m testing recipes or trying new ideas, I approach it like an experiment.

I love the idea of food as comfort, as something you enjoy that’s still deeply rooted in home. That brings me conveniently to my next question. You started Kitchen Butterfly as a way to document recipes, especially for your children, as a deeply personal project. When did you realise that this was more than just something for you and your family? That it was bigger, something about community, memory, and maybe even cultural preservation?

For a long time, it really was just about me. I was on this journey, looking for Nigerian recipes that didn’t exist in the way I wanted. So I started writing my own versions, documenting them so I could come back to them later.

A huge shift happened in 2011. I had just moved back to Nigeria from the Netherlands and reached out to an American website to pitch an idea. They replied, “Sorry, we don’t take unsolicited pitches. We commission writers.” I was really ticked off.

I thought, "What do you mean? You have a website that barely reflects any diversity, and I’m offering you something fresh." I was angry. But then I redirected that energy. I thought, "Why am I casting pearls before swine?" I could just build my own platform, create my own knowledge base, and document what I was doing for myself.

Somewhere in my mind, I always knew I wanted to write a cookbook. At the time, I wasn’t even sure if it would be Nigerian-focused. But I knew Nigerians needed this information, we shouldn’t have to search for things like the information in seasonal produce calendars. This knowledge should be readily available. And not just for others, for me too. My head was full, and I didn’t want to keep it all in there. I wanted a place where I could return to it easily.

Eventually, people began to reach out with messages and questions, and I started to feel a small sense of community forming. But it’s funny; with blogs, only a tiny percentage of readers actually comment. You could have thousands of views on a post and not even five comments.

Community, for me, means call and response, dialogue. But I could still sense that people cared about the things I was writing. They’d engage with me more on platforms like X (Twitter) or Instagram, where communication was easier and more immediate.

So I’d say I found a stronger sense of community through social media than directly through the blog. Still, I saw that people were responding to my experiments, my photography, my writing, whether it was rooted in classic Nigerian cuisine or a newer perspective I was bringing to ingredients.

That makes perfect sense. You mentioned that at the time, you weren’t really thinking about starting a cookbook, although it was somewhere in the back of your mind. And now, you’ve written Chop Chop, the Cookbook. You’ve written this, and it’s more than just a recipe book; it’s essentially an archive. What was the emotional journey like in creating something so expansive and rooted?

It was traumatic in parts. I’d do it again. I have zero regrets, but it was hard for many reasons.

I went into the process really confident. I had written a book proposal where I clearly laid out my ideas and vision, and that’s what helped my agent secure a book deal with publishers. Because of that, I felt assured, I knew what I wanted to do and where I was headed. I thought it would be easy. I know Nigerian cuisine and culture well, so I didn’t anticipate any major issues.

But once I sat down to write, even with a solid table of contents and a clear roadmap, I found myself deviating from that plan, even though I was still focused on the same end goal.

One of the first things I noticed was that some of the things I was confident about were suddenly being called into question, like the botanical names of herbs. Documentation around Nigerian cuisine is often inconsistent. You’ll see ingredients labelled incorrectly, and those errors get repeated across websites and platforms. You don’t even realise your source is wrong. I’d come across the name of a vegetable I thought I knew, only to find I couldn’t confirm it with a reliable, primary source.

That brought up doubt. Was I even sure of what I was doing?

The second thing I noticed was that I was writing in absolute terms, “Nigerians do this,” “Nigerians eat that.” But the more I wrote, the more I researched, and the more conversations I had, the more I realised there are no absolutes. At best, I could say, “I’ve seen Nigerians do this,” or “I’ve heard that.” Blanket statements didn’t work. That shook my confidence, too. I’m Nigerian, I thought I knew us.

Eventually, I realised there’s a way to approach this work with humility. You can honour what you do know while giving space to what you don’t. That shift helped me change how I thought and wrote. I became more intentional about using language that reflected my knowledge while leaving room for other experiences and interpretations.

And where I didn’t know something, I asked. When working on recipes from northern Nigeria, I reached out to friends from the region and asked questions. I brought in as many cultural experts, friends, and sources of knowledge as I could because I wanted to do it justice. I wanted this to be a seminal work, something instructive not just for Nigerians, but for West Africans and even non-Africans, to see the beauty, richness, and value of Nigerian cuisine.

Those were some of the key things on my mind during the process.

That’s interesting to think about, I can only imagine! How long did it take to write the book?

I started working on it in 2019. But I’ve been writing about Nigerian food for what, 16 years?

I can imagine it must’ve been an emotional rollercoaster to finish the book.

You mentioned something earlier about how you can't make blanket statements about Nigeria. As we know, Nigerians are incredibly diverse, with multiple cultures and ways of doing things. And there’s that classic saying, “In my house, we do it this way.” Yet you were also trying to span the different regions of Nigeria, highlighting both iconic and lesser-known dishes. So, how did you decide which recipes and stories were important to include?

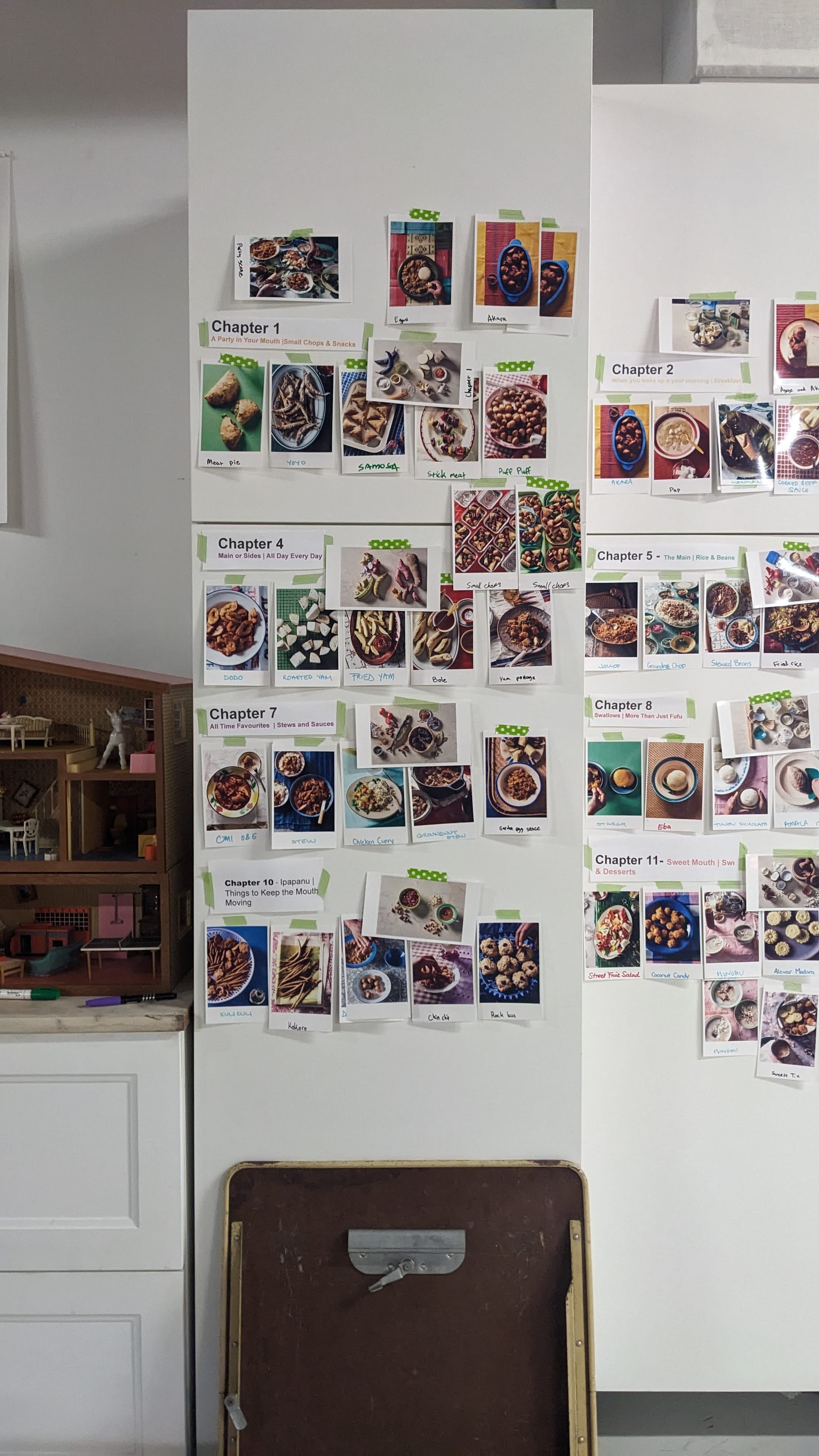

At this point, I did a brain dump of all the recipes I knew, ones I’d eaten, discovered, and remembered. That was my starting point: this massive brainstorm. I’d kind of had that list in my head for a long time, mentally working through the different regions and dishes. Once I got everything down, I created buckets, like breakfast, snacks, and started refining the recipes.

Some of the categories actually started changing as I went. For example, I originally grouped soups, stews, and sauces together. But as I started writing the headnotes, the introductory parts of each recipe, I realised that stews and sauces were typically paired with grains, cereals, and vegetables, while soups were usually eaten with swallows or soft doughs.

So it made sense to separate them. When I think of Nigerian soups like egusi, ogbono, or okra, the primary context is eating them with swallows. Sure, some people eat them with rice or plantains (I eat Egusi soup with rice, I eat Banga with rice), but the primary use is still as an accompaniment to swallows.

Then I looked at stews, they’re more often paired with plantains, yams, and rice, so they felt different. Even though I started with a certain structure, I ended up breaking it down differently as I went along.

Another example is snacks. Initially, I grouped all snacks and small chops together. But then I started thinking about context. Small chops, samosas, spring rolls, puff-puff, are so tied to parties and celebrations in a way that everyday snacks aren’t. You might still see chin chin at a party, sure, and yes, I eat puff-puff at home too. But there’s something distinctly festive about that small chops spread.

So the chapters evolved as I thought through not just the food, but the cultural and contextual meanings. It wasn’t just about writing recipes, it was about stepping back, being critical, and asking, “Do these categories make sense?” In doing that, the clarity came even if I didn’t start out thinking in terms of regions or themes.

Yeah, that makes sense. And when it comes to different regions and places, how do you decide, “Okay, these are the recipes I’m going to do,” or “These are the ones that represent these people”?

I knew I had a broad knowledge of Nigerian cuisine. I had either eaten or engaged with ingredients and dishes from across the six regions. For example, I have a friend, Ngozi, in Jos who runs a fruit and vegetable company called Earth Fresh Foods. Through her, I discovered ingredients from Plateau, things like dried sweet potatoes or rice still in its husk, which is sometimes used in kunu.

Then I have another friend, Ellen, who is Tiv, and her mom gave me all sorts of ingredients like ground millet mixed with spices, which they use to make a breakfast porridge called Ibyer. All of this happened before I started writing my book, so I already had a pretty good sense of Nigerian cuisine on both national and regional levels.

I love that. Moving beyond your cookbook and into your broader work around the global imprint of West African food, I wanted to ask: What are some of the connections you’ve seen between West Africa and the diaspora when it comes to food? And what does that connection mean to you personally and to people who are interested?

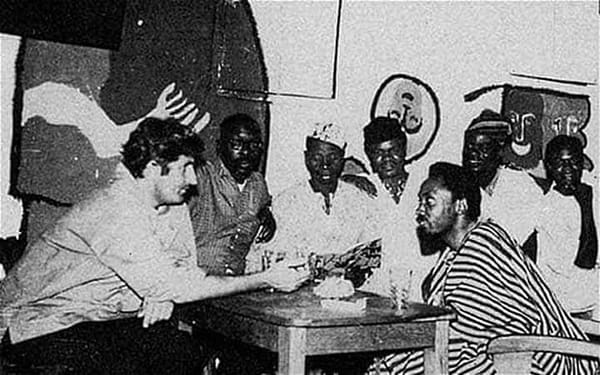

I think it has a strong connection to heritage, legacy, and language. Take Akara, for example. Over the last few years, I’ve been working on an atlas of foodways and foodways connections, and Akara is one of those dishes that appears across the Black Atlantic. You’ll find versions of it everywhere, from West Africa to the Caribbean coast, all the way up to the American South. And many of those versions still honour the name: you’ll see it called acarajé, akala, calas, the language links are very strong.

The similarities are significant, but there are also differences shaped by geography and availability. In Nigeria, Akara is made from black-eyed beans or cowpeas, the same as in Brazil. But in other places, it might be made from taro, cocoyam, pumpkin, fish, salt cod or rice. Basically, people used whatever ingredients they had, but the core remained the same: a batter or dough that was deep-fried into fritters. That continuity in name and form helps you trace an edible trail all the way back to West Africa.

I’ve written pieces about these shared connections. It’s important to me to highlight this for several reasons. First, people often question whether Nigerian or West African food has history or legacy. But it does, our food has left a mark. It has influenced cuisines across the world, and while we’ve also been influenced by others, we’ve absolutely done the work of shaping global cuisines too.

There are also many dishes that reflect these connections beyond the transatlantic enslavement of West Africans. In the case of Akara and acarajé, yes, that link is rooted in the forced migration of enslaved West Africans. But the fact that these foods endured, that they evolved while still preserving their essence, is a form of protest, resistance, and cultural survival.

Even when our people weren’t allowed to write or document, they passed down these foods. That, to me, is incredibly powerful.

Another example is curry powder. In Nigeria, we make a kind of chicken curry, and you’ll find similar curries in Korea, Japan, the American South, and other parts of Africa. In that case, the connection comes through British colonialism, and curry powder as a blend has become a global construct. And that, too, gives us a way to look at both the similarities and subtle differences in food cultures around the world.

That’s beautiful to see. You live in Canada, and I want to know how you keep those ties to your cultural roots. I mean, you wrote most of your book while abroad. You may have been travelling, here and there, but you weren’t based in Nigeria. So, how do you stay connected to your roots and your culture?

It’s like asking, "How do I keep myself?" I’m Nigerian through and through. There’s no day I’m not Nigerian. It’s baked into who I am. I eat Nigerian, I drink Nigerian, everything I do is through the lens of being Nigerian. That means there’s almost always stew in my fridge or freezer.

One way I stay close to home is by surrounding myself with Nigerian things, whether that's books or ingredients. I also built a mosaic of sources to meet my needs for Nigerian food. That means finding similar ingredients at regular grocery stores or going to speciality stores that cater to other cultures with similar food traditions.

For example, if I want certain cuts of meat and can’t get to a Nigerian store, I’ll go to a Chinese shop. If I’m looking for smoked mackerel, sometimes I’ll go to a Polish or Eastern European store. Writing the cookbook helped me create a kind of map for myself, where to find Nigerian ingredients and their best substitutes, because that’s the reality of living away from home.

I also support Nigerian stores online and sometimes even order ingredients or food directly from Nigeria because I crave a particular taste. It’s all part of my journey as an adult, piecing together different parts to make the whole. And honestly, I crave Nigerian food often. Thankfully, things like plantains are easier to find now; they’re always in the shops.

Speaking of roots, how do you think food can serve as a bridge between the past and the future? Especially considering the work you do with Feast Afrique. I’m such a big fan of the historical references you share. How do you think food connects us to our history and also helps guide younger generations, both here at home and in the diaspora?

That’s such a beautiful question. When I think back to my work as a geologist, one of the key principles is uniformitarianism, the idea that the present is the key to the past. Geology studies processes over time. Layers of sediment build up, and by studying what we see today, we can understand what happened in the past. Each layer tells a story: the top layer is the youngest, and the deeper you go, the older it gets.

It’s the same thing with food. I can look at what we’re eating today and work backwards. That’s part of what I love about cookbooks; they help map out the evolution of Nigerian cuisine and culture. I once came across a Nigerian cookbook from 1910 that spoke poorly of local eggs, saying they were so bad they were only good for throwing at people during elections, which, interestingly, ties into the global history of egg-throwing during protests.

But by 1934, you start to see eggs appear in actual recipes. My research revealed that during the Great Depression in the 1930s, colonial governments promoted eggs in African diets to combat malnutrition. It was a quick fix, eggs as a protein source. So today, when we see eggs in so many Nigerian dishes, few people realise this practice stems from colonial nutrition policies over a century ago.

That’s the power of food; it tells stories. Recently, a friend, Dorothy, gave me a special kind of salt from Cross River. She explained how families take turns harvesting it during the dry season. I became curious and found academic papers on the politics of salt in Cross River during colonial times. Everyday ingredients like salt aren’t just kitchen staples, they hold deep cultural and historical meaning.

Because I know who I am as a Nigerian, when I meet people who try to challenge that, it doesn’t faze me. Maybe when I was younger, I could be swayed, but not anymore. I know who I am. Part of that confidence comes from knowing we have history, we have culture.

West African knowledge, not just labour, was instrumental in transforming other continents we went to. People were stolen from West Africa not only to work the land but also because they had the agricultural expertise, like growing rice in swampy areas. That knowledge shaped the American South’s rice industry.

So when people reduce the transatlantic enslavement of West Africans to just “labour,” they miss the full picture. Our ancestors brought intellect and skill. And when you look at global migration today, you see echoes of that, countries seeking skilled immigrants to boost their economies. The system isn’t as brutal, but the premise remains: people are valued for their knowledge.

That’s why the geological framework, the present is the key to the past, still shapes the way I think about food. It’s not just about ingredients; it’s about history, culture, and identity.

That’s such an interesting point, and I think it's super important. It’s hard to find proper documentation, but the more I get exposed to work like yours, the more I see, we do have deep roots, we do have history, and we did and do have intellectuals. We had people who shared knowledge. And I think it's so important, especially for the younger generation, to realise that.

My niece was looking for a particular cassava chip called Abacha Mmiri, but she only knew the name in Rivers, where it's called Bobozi. She was trying to explain it to her friend: “This thing my grandma used to make for me.” She goes online, searches the name, and what comes up? A reference to my blog. And in that blog post, I’m talking about the same thing her grandmother gave me. That was such a full-circle moment.

My niece, living abroad, just wanted a taste of home and a way to connect with a friend. She only knew that one local name, and thankfully, she found a resource. That’s one of the greatest joys for me. We have to leave those trails for the people coming after us.

I absolutely love that story. Now that you’re a professor, someone who teaches and does public work, what are some of the powerful responses you’ve received in relation to food and your work?

A lot of my work is in food, travel, and tourism studies. As much as I can, I bring in shared foods and drinks. When I teach, I always look for examples that show similarities across cultures and cuisines.

Some students are amazed to learn that Nigerian food isn’t all spicy or peppery. They’re surprised to see that our food shares similarities with what they know. And many are curious about how I transitioned from geology to gastronomy.

I’ve received really great feedback about Chop Chop and my other projects, how they teach people, shine a light on Nigerian cuisine and culture, and use language to create global understanding. People often ask, “Where can I get the ingredients?” And I’m like, “Everywhere!”

I’m not saying you have to struggle to find Nigerian ingredients, but when I cook food from another culture, I take the time to invest in finding the right ingredients and learning the recipes. I know I’m the exception because I love food and that process of discovery. But still, I’d like people to do the same for Nigerian cuisine. You can always ask me questions, but you can also do your own research.

That’s why I’m so passionate about documentation. The more knowledge we preserve, the more references people will have and the more they’ll see Nigerian cuisine and culture as something worth exploring deeply, with pride and agency.

And there's so much joy in discovering that kind of information about yourself. It gives you a real sense of accomplishment. My final question is a personal one: What are some of your favourite comfort foods and drinks?

My favourite? Soaking garri. I think soaking garri is number one! I think about puff-puff a lot. I don’t make it too often because I know if I do, I’ll eat too much of it. But it’s definitely a comfort food. Pounded yam and egusi, yes. Or pounded yam with okra stew. Not often, though. With drinks, definitely zobo or Chapman, top of my list. And palm wine. Sometimes I think about palm wine a lot. Sweet, fresh, straight from the tree, before it has a chance to sour. That creamy sweetness, that slight booziness. Beautiful.

Thank you. This has been so much fun. I’ve learned so much and really enjoyed the conversation.

Member discussion