Founded nearly a decade ago, The Wine Club Lagos has become a defining force in Nigeria’s evolving wine culture, shifting the conversation from wine as a luxury symbol to wine as a shared cultural experience. At the heart of this movement is Folakemi Alli-Balogun, a wine educator, cultural curator, and founder whose work blends education, storytelling, and creative expression to make wine more accessible and meaningful in Lagos.

With certifications from the Cape Wine Academy and WSET Level 2 (with Distinction), and as a recipient of the Bordeaux Mentor Week global wine scholarship, Folakemi brings global wine knowledge into a local context. Through The Wine Club Lagos, now a community of over 500 members and 50+ tastings strong, she has steadily redefined how Nigerians learn, taste, and connect through wine.

That vision reached a new peak in November 2025, with Symphony of Wine and Sound, an unprecedented multisensory experience pairing six internationally curated wines with original live orchestral compositions performed by a 20-piece ensemble at the Metropolitan Club. Created in collaboration with Vesta Orchestra, the event explored a simple yet radical question: what does wine sound like? Guests were invited to experience wine through tone, rhythm, memory, and emotion, resulting in moments that felt deeply personal and collective at once.

In this interview, Folakemi reflects on her journey into wine, the power of community, and her belief that wine has a voice everyone instinctively understands. We discuss the making of Symphony of Wine and Sound, the creative risks behind it, and how she continues to reshape Nigeria’s wine narrative, one experience at a time.

So I always start like this. My first question is just for you to tell me about yourself; your background, what you enjoyed as a child, what you studied, and how you basically found yourself on this path that you’re on.

Okay, good question. I come from a family of three with an older brother and a younger sister. My dad was a banker, my mum a lawyer. I don’t really remember what I wanted to be as a child, but I was chatty, free-spirited, and for a while the baby of the house. I was very different from my quiet, introverted brother.

People always told me I’d make a good lawyer, and for some reason, I hated that. I didn’t like being predicted or boxed in. So when it came time to choose subjects in secondary school, I deliberately went the science route, just to move as far away from law as possible. I continued with sciences all through secondary school, and when it was time for A-levels, I told everyone I wanted to be a doctor. Deep down, I didn’t care about it; I just thought, if this is the path, I could do it.

Then, my mum had me speak to her sister, who’s a doctor. She asked if I was really sure about medicine, and that conversation somehow led me to pick the same subjects as my brother, who was already studying law. That’s how I ended up on the path to studying law.

At first, I struggled a bit, but eventually, I got the hang of it. My mum was thrilled. Even though I didn’t have a deep passion for it, I thought, “I can do this.” At university, I actually grew to like law; the training sharpened my critical thinking and communication, but I knew I didn’t want to pursue it as a career.

I went to law school, but was already plotting my escape. I chose a master’s in international business and global affairs, hoping to shift people’s perception of me, but it didn’t quite work. I practised law for about a year during NYSC, doing the full spectrum: court, company secretarial work, everything, then I stopped, looking for something different.

That led me to PwC, one of the Big Four accounting firms, which marked the real start of shedding the “lawyer” label and exploring other paths.

Thank you so much for sharing. There are so many things that I’m sure many Nigerian children can relate to. You later got into a different path entirely: wine education, cultural curation, and consulting, which I believe you must have started exploring from the time you found yourself at PwC. So I wanted to know what those early experiences were like, whether personal or professional, that shaped your curiosity about wine and the cultural space, even before you went on to formally study it.

I’ve always had a creative streak. From primary school through secondary school, I was involved in everything—drama club, singing, debating. Whatever extracurricular activities were available, I was part of them.

I never aimed to be a singer or actress, but I’ve always expressed my creativity in different ways. At the time, I wasn’t thinking about wine at all, but I knew I wanted to do something beyond my professional work, even if I couldn’t articulate it. People around me could always see it.

I also resisted others trying to define my path; just because I was at PwC or practising law didn’t mean they could tell me I should go into marketing or public speaking. I always had some creative outlet growing up, and I think that’s where it all started.

That makes sense. So what would you say inspired you to go on and study, or train, specifically in South Africa, and also with the WCT?

That’s a good question. I officially launched the wine club in 2016, though the idea came to me in late 2015. Honestly, it just kind of happened. A friend suggested I start a wine club; neither of us really knew what that meant, but it sounded like something I wanted to explore.

Luckily, I had a trip planned to Cape Town that Christmas, so I visited vineyards for inspiration. It was beautiful and inspiring, but I still wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. When I returned, I decided to just launch. I invited my friends, emotionally blackmailed them a bit, and they came. If you’d asked me that day, “What’s the wine club?” I’d have said, “I don’t know, I just launched.”

Soon after, someone asked if I’d do a wine-and-steak pairing. I don’t eat red meat and didn’t know much about steak, but I said yes. It gave me a starting point; I had to learn about wine, about pairing, about tasting. I created a tasting with three wines and three steaks, invited people, and it came together.

I did feel imposter syndrome or maybe just genuine uncertainty. I didn’t know where to get the right wines; I’d pick bottles that looked interesting or were recommended somewhere. Early on, someone in the culinary industry asked if I was a sommelier. When I said no, she discouraged me from starting the club. That knocked my confidence. I wondered, what if people ask me for my credentials?

Still, I carried on. I’d tell people, “Nobody’s claiming to be an expert,” until a friend told me I shouldn’t say that. She suggested I get a certification. At the time, what I earned made it difficult, but I found a course and took it during another Cape Town trip. I learned a lot, especially about South African wine, which gave me a strong foundation.

Alongside that, I kept learning online, reading, tasting, and visiting vineyards. Gradually, things came together. Eventually, I pursued a WSET certification because I wanted a globally recognised qualification. The wine club was growing, and people were beginning to see me as a wine expert. I wanted to ensure that when people asked about my training, I had something credible to show, and that’s why I went for it.

Thank you so much for sharing that. There were so many layers to it, and I’m really glad you found the confidence to keep moving forward despite the discouragement. And I think that brings me to my next question.

You started the wine club from just an idea, and then you kept building on it. Now it’s been about ten years. Your club has grown beyond sharing wine to learning, curiosity, and even expression through wine. So I wanted to ask, what was the moment that made you realise that Lagos needed wine education? Not just consumption, not just “let’s drink wine,” but something deeper.

I don’t think it was a single moment. Early on, I realised that at my launch, I didn’t fully know what I was doing. But people were curious, and I wanted to move beyond just steak pairings and do something different.

That’s when I came up with the idea of a blind tasting; pouring wine without people knowing what it was. I noticed that when people see a bottle, they sometimes judge it before tasting. A blind tasting removes that bias.

I set up an experiment with three reds and three whites, giving people descriptions and asking them to match the taste to the wine. I even turned it into a little competition, collecting their answers and announcing the winners. The reactions were amazing, people loved it, celebrated when they got it right, and often said things like, “I learned something today” or “I had no idea.”

It wasn’t just beginners; sometimes it was people who’d been drinking wine for decades. Seeing those responses consistently made it clear that the tastings should be about educating people, helping them discover something new about wine. That’s really what it became.

Thank you. And in that same vein, you hosted an event this year called Symphony of Wine and Sound. I found it really interesting that you chose to merge wine and drinking with music. I’d love for you to take us through that process, from coming up with the idea to actually working with an orchestra.

People often ask me, “With the wine club, your tastings aren’t expensive. How does it work?” For me, the key isn’t money, it’s who joins. I’m very selective. Yes, there’s a form and a few questions, but really, the main criterion is that I like you. I’m not looking for experts, just people who are easy to talk to, enjoy the events, and won’t make others uncomfortable.

People also ask, “How do you make money from this? What’s the end goal?” When I started the club, it wasn’t about profit; it was a creative outlet. I had no interest in importing wine, opening a shop, or running a wine bar. The truth is, in Nigeria, the infrastructure and culture just aren’t there to sustain it. Running a wine bar requires constant traffic, inventory management, staffing, and overheads and that can easily turn passion into work. My tastings let me focus on what I love without being consumed by everything else.

I wanted to create experiences, ways for people to engage with wine differently. About three years ago, I watched my cousin’s teenage band perform in London, and I was inspired. That’s when I asked myself: what does wine sound like? Could I create an experience that combined wine and sound?

I started planning. Last year, I pitched the idea to a few companies, but it didn’t gain traction. This year, I made it a personal goal: I’m doing it, no matter what. Ideally, I wanted full funding first, but a friend told me to move in blind faith. A month before the event, I didn’t even have half the money. Still, I kept going.

I engaged the orchestra early, teaching them to taste wine and documenting the process. I was supported by incredible people, my “angels”, who backed the project without knowing exactly how it would turn out. Even I didn’t know the full path. But we believed in each other, and through that shared faith, we made it happen.

Thank you. What was that like, taking the orchestra right from the beginning and then having them translate that learning into music?

I had no doubt that if I taught the orchestra well, they would get it and make the musical associations, because I had already tested the idea. Last year, I invited a musically gifted friend over, laid out some wine, and showed him how to taste it—how to identify its characteristics. In less than an hour, he was already making associations. He didn’t have the terminology, but it was clear he understood.

I thought, if he can get it, a whole orchestra can. I ran two full training sessions, and it went seamlessly because I had carefully planned everything. I broke things down using resources from the WSET, the way I was taught, and walked them through the Systematic Approach to Tasting Wine. It’s not arbitrary, and they all understood. They could describe the sensations, the characteristics, how it felt in the mouth, on the tongue, all of it.

It was fascinating, and we captured the whole process in the documentary.

Interesting. And just before I move on to my next question, I really enjoyed you speaking about moving in blind faith and just starting. I feel like many times, we tend to overthink, strategise, write a plan, rewrite the plan, and still feel stuck because we can’t fully see what we’re doing. But once you begin, you realise you actually have a way.

You’ve talked previously about how wine has a voice and how everybody instinctively understands that, even though it can mean different things to different people. What reactions did you get during the performance or the event that affirmed that belief for you?

Before the performance, at one of my tastings, I pulled aside a few members and asked, “What do you think this wine sounds like?” I didn’t use any systematic approach; I just asked. This was captured on film, and I’d had similar conversations before, so I knew people would make associations, even if they weren’t the same. It’s all subjective. Some go very left field, but often those people aren’t regular wine drinkers, or they overthink it.

Mostly, people respond in similar ways. For example, Bordeaux wines are deep, bold reds, so people associate a deep sound, some say double bass, others saxophone. Someone even made a sound on the spot, and I thought, absolutely, that makes sense.

Going into the performance, I knew people would think along certain lines. During the event, I gave clues and pointers, and there weren’t strong disagreements; more of a spectrum of responses. In the documentary, you see people nodding, saying, “Oh, that makes sense.” Some don’t make any association between wine and sound, which is fair. But for the most part, it’s all about memory.

I remember watching the video and seeing people go from wanting to dance, to recalling a childhood memory, to remembering that they were reading a book. I found that really interesting. And you mentioned community, you’ve built a growing one. You have more than 500 members and have hosted over 50 tastings. So I want to know what shift you’ve observed in how Nigerians engage with wine now. Have the types of questions changed? Has there been a shift in curiosity or misconceptions compared to when you first started? Even within the industry, would you say there’s been a shift?

With my members, at each tasting, there’s always curiosity; they want to know, and many have noticed how things have changed since they started. But at any tasting, there’s sometimes someone completely new. For example, at tasting number 48, it could be someone’s first time. Their questions might sound like those of long-time members, but everyone isn’t moving at the same pace.

That said, I do see growing curiosity and interest in wine compared to when I first started. Every week, I meet someone who says, “I like wine, but I don’t know much about it. I just enjoy drinking it and pick a label blindly.” More people are coming of age, drinking responsibly, or being exposed to different wines. Growth is definitely happening.

There’s also been a shift in perception of Nigeria as a wine market, though it’s not driven by our knowledge alone. Globally, wine consumption is declining in traditional regions, so producers are looking to new markets. Africa, and Nigeria in particular, has become interesting. If people enjoy champagne, they likely have a taste for wine too.

With education and exposure, Nigerians can gradually expand their tastes beyond sweet wines toward drier styles. We’re growing, and people are noticing. Producers are starting to see our preferences and catering to them, though there’s still so much untapped potential.

That’s good to know. On educating and shaping consumer knowledge, your documentary will be a major way for many people to be exposed to wine or learn about it. What do you hope it reveals about African creativity, collaboration, and the definition of luxury for Africans and Nigerians?

I don’t want people to see wine as a luxury. The goal is to make wine approachable and spark curiosity, especially for those who’ve never tasted it. Many orchestra members had never engaged with wine before, yet once I broke it down, their interest piqued.

It’s not about luxury; it’s about showing that even though we’re not producers or the biggest consumers, we can appreciate wine as an art form, put our own spin on it, and share it with the world. Nigerian creativity inspired this approach. When I spoke to the orchestra, no one said, “That’s impossible.” Everyone immediately started thinking, “How can we do this?” It reflects the Nigerian spirit: we believe we can do anything.

The documentary also invites music lovers and non-wine enthusiasts to think differently, to associate wine with music, memories, and experience. It’s about thinking outside the box and appreciating wine in new ways, beyond traditional wine or luxury circles.

From the start, you’ve made it clear you want to move away from the notion of wine as just a luxury, which I really appreciate. I also love how you mention curiosity. My last question is, now that you’ve blended wine, music, and memory, what other cultural intersections are you thinking of exploring next? Food, dance, art, literature?

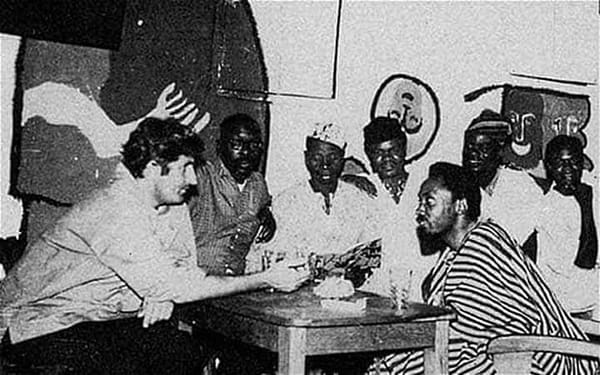

Honestly, who knows? Last year, I hosted a tasting with Professor Soyinka, who’s famously said, “I’d rather drink wine than water.” At the tasting, he even said, “The less time we spend talking about wine, the more time we drink it.” It was really fun.

For me, my attempt is to associate wine with other creative processes. For example, how can the process of making wine be juxtaposed with writing a book? Honestly, I don’t know what’s next, but creative ideas around wine are never far from me. Even with my regular tastings, I don’t know what the next one will be, but when it happens, it’s exciting.

Thank you!

Member discussion