Violeta Sofia is an award-winning artist, photographer, and activist whose career defies easy categorisation. Born in Cameroon and raised in Spain, with roots in Equatorial Guinea and a creative life shaped in the UK, her work is just as layered and complex. Over the years, she has exhibited at major institutions including the National Portrait Gallery and Christie’s, while her portraits and fine art photography have appeared on the covers of Elle Italia, Deadline Hollywood, and The Telegraph Magazine.

What sets Violeta apart is her ability to weave together technical mastery and emotional depth. Inspired by the lighting of the Old Masters yet refusing to be confined by their Eurocentric traditions, she has developed a style that is both classical and radically new. Her acclaimed Hand Masters series, for instance, transforms the reality of living with vitiligo into powerful, poetic imagery that sits at the intersection of photography and painting. In her work, hands become flowers, symbols of growth, individuality, and resilience.

But Violeta’s practice extends far beyond aesthetics. A committed advocate for representation, she has pushed for greater visibility of Black and female artists within spaces like the National Portrait Gallery. She sees art as dialogue, collaboration, and change.

In this conversation, we discussed her journey from taking photographs at eight years old to showing at the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, her reflections on belonging across cultures, the evolution of her practice, and how she continues to break boundaries between art forms, identities, and traditions.

You were introduced to photography quite early, at around eight years old, with your first camera. From those early days to now, what do you miss about that time, and what has that transition into where you are now been like?

When I look back, I feel very proud that I never stopped. From a very young age, I knew I was creative, but being an artist isn’t always supported by society, parents, or even friends. It can feel tough when your career choice isn’t fully understood. So, when I revisit my early work, what I see is determination. I see someone who didn’t give up, and that gives me joy because I’ve been able to keep doing what I love.

In the beginning, I think I was trying to fit in. You copy, you imitate, you’re influenced by what your teachers show you, which isn’t always the work you would have naturally gravitated toward if left on your own. So my early work carried those influences, and in some ways, it still does. But now, I try to be more intentional about drawing inspiration from artists of colour.

Because of my education and the way I was trained, my references were very male-oriented, often white male photographers. That shaped how my art grew. Even when you try to expand, it can be difficult to unlearn those frameworks and bring in new perspectives. But what excites me now is seeing more female photographers, more African and Black photographers; there’s been a real shift. Even if my own work still carries traces of that earlier education, I can feel that change happening through the new voices and the new generation.

That’s a great way to start, as you touched on a number of themes I’d like to get into. Recently, I saw a caption where you said you’ve been described first as a Cameroonian artist, then as a British artist, and then as an artist from Spain. You explained that Cameroon, your birthplace, grounds you in heritage and tradition; Spain shaped you through a traditional education; and in the UK, you found freedom to be honest with yourself. Could you expand on that?

Thank you for picking up on that. I’ve become more personal on Instagram, but you never know who’s really reading, so it’s nice to know that you are.

That caption came from an exhibition where my work was taken to Dubai. Every time I go to a new country, I feel I become a different version of myself. I was born in Cameroon, but we moved to Spain when I was less than a year old, and my father is from Equatorial Guinea. So from the start, I was Cameroonian and Spanish. Then, when I moved to London, I became Cameroonian, Spanish, and English. And now, when my work travels to places like Dubai or Saudi Arabia, I’m introduced yet again in new ways. People there will ask: “Is your work British? Is it Spanish?” But what I love is that in those places, they are really pushing forward African, Asian, and Arabic art.

It’s interesting to step outside of Europe and realise that Europe isn’t the centre of the world. In places like Dubai, people are more curious if I say I’m African than if I say I’m Spanish, because that’s what they want to celebrate. One of the galleries that represents me lists me as Spanish, which I found very interesting. It made me realise that my identity shifts depending on where I am. In England, I’m usually seen as Spanish and Cameroonian. Outside England, people tend to see me as British and Cameroonian. It’s all these layers that keep building on who I am.

At my core, I feel African; that’s my roots, my parents, my food, my culture. But Spain shaped my language, my expressions, the way I communicate and think. And then the UK gave me freedom. It gave me the support I needed to grow as an artist.

Thank you so much for sharing. I think that was super insightful into your creative process and journey. You also talked about wanting to research African art and heritage, even though your education wasn’t inclusive of that. How were you able to connect with your roots from Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea, and how has that shown up in your work?

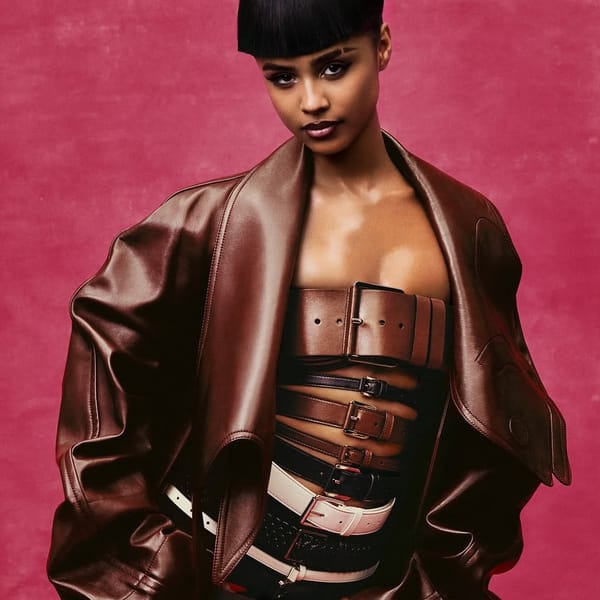

So, my work is split: I’m a portrait photographer, but I also do fine art. With portraiture, many of my sitters are white, and I’m proud of that, but in my personal projects, I focus on people of colour, mainly Black sitters. Then there’s my Hand Masters series, where I use flowers and my own hands with vitiligo. That work connects to the old masters, which makes it easy for audiences to engage with, but once you look closer, you see something new: my hands, my story.

Bringing in my Africanness has been more complex. I didn’t grow up in Cameroon, so I often wonder: how do I tell that story? And will people from Cameroon accept it as authentic? When I visit, people immediately know I’m not from there, so there’s always this tension of belonging.

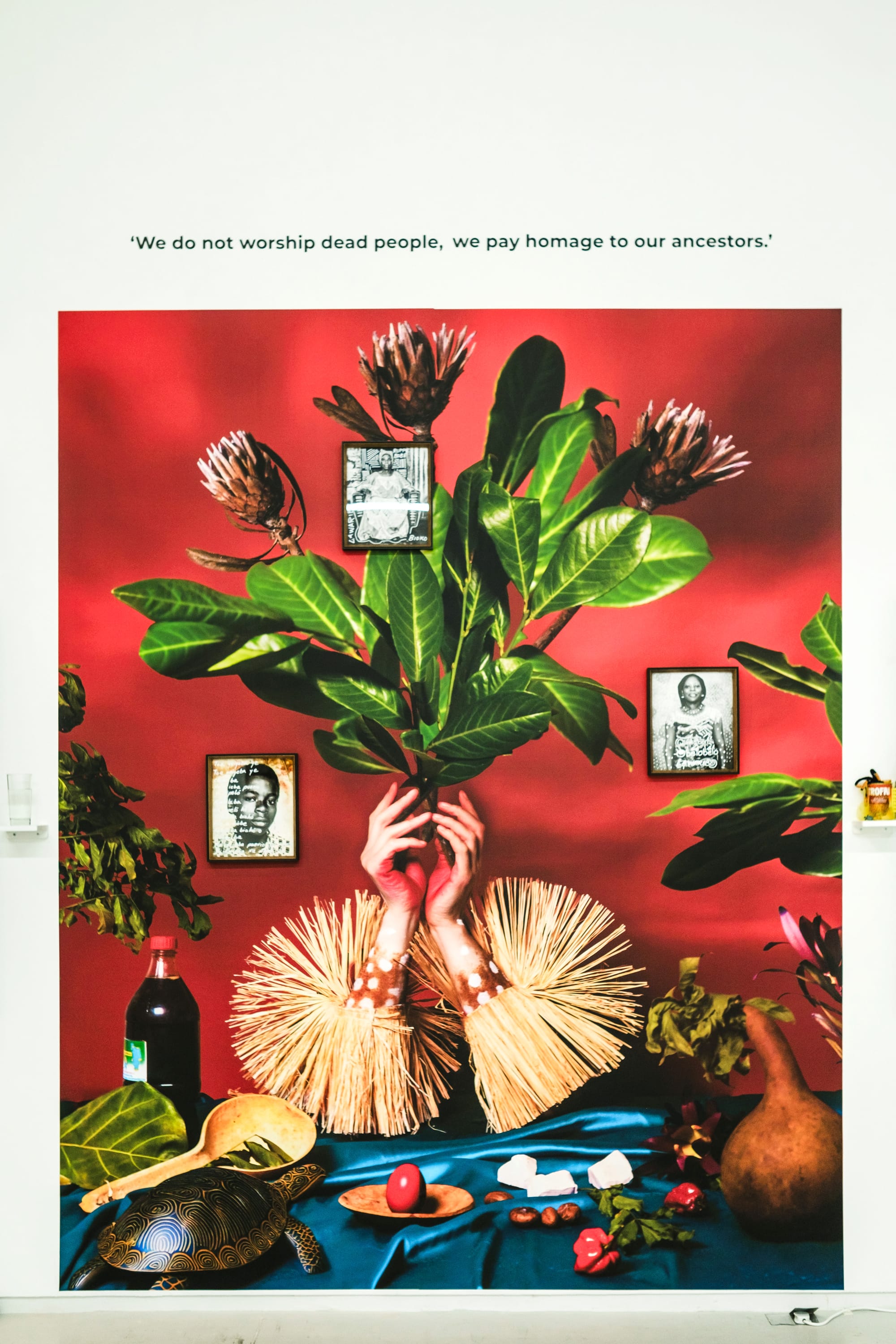

One project, Belonging and Rebirth, came from listening to my parents share traditions and practices from home; rituals, connections with nature, herbal knowledge and the rest. In Equatorial Guinea, nature is at the centre of life, but here in Europe that connection feels lost. So I used flowers and plants to tell those stories, even though it was difficult without access to tropical plants. In a way, making that art became a way of rediscovering myself.

But it also showed me how much has changed. My parents left decades ago, so some of what they taught me doesn’t exist anymore. Cousins back home don’t know the same traditions or speak the same languages. So I realised I was creating an imaginary world from fragments of memory. At the end of the project, I thought I was going to feel more rooted, but instead I realised my belonging is different.

One of the central colours was red, inspired by a baptism ritual in my tribe where newborns are washed with red leaves. Red became a symbol I could carry forward. In the exhibition, I had a red oak tree, a European tree painted red, and I connected with it deeply. That was the revelation: I don’t need to chase a past that isn’t fully mine anymore. I can carry the red with me wherever I go, transforming it into my present. It’s a form of self-healing.

I think it can be bittersweet, but we always have to remember that everything changes.

Exactly, things change, and so do we.

Touching on that, you mentioned earlier the importance of seeing more representation, especially women of colour in art. You’ve also been active in pushing galleries to include underrepresented artists. How does that feel for you? What does that sense of community and inclusion mean?

For me, the only way forward is through community; bringing people in, sharing, and supporting one another. And I don’t just mean sharing work, but also sharing conversations, being open about what we’re going through. Because being an artist is lonely. It’s unregulated. No one teaches you the practical things: contracts, rates, or how to navigate the business side. You just learn as you go, often alone. That’s why it’s so important to create groups, to have people you can talk to, and to support each other where you can.

When I entered the National Portrait Gallery, my artistic name, Violeta Sofia, meant people didn’t necessarily know my background. When they accepted my work, I had sitters who were all white, which is fine. But as I stood in the gallery looking at the walls, I thought, “Where are the women of colour?” It was a female-focused exhibition, so I asked if I was the only Black woman included. Turns out, there was just one other, and she had passed away. That was a striking moment.

So, I made a proposal. I put forward 25 names to start. To their credit, they openly listened and expanded the exhibition. Suddenly, you didn’t just have Black photographers, but also Black sitters, sitters of all backgrounds. And importantly, it wasn’t stereotypical. Black photographers weren’t only photographing Black people. You had Asian photographers photographing Black sitters, Black photographers photographing white sitters, and so on. That was exciting to me because representation shouldn’t be limited or boxed in.

I like creating positive change. I don’t like stagnation. I’m always asking, “Okay, this is good, but what’s next?” That exhibition was one step, but more change is still needed across different areas.

Thank you so much for sharing. I know this is deeply important, and it’s encouraging to see institutions responding and making space.

And it mattered that it was the National Portrait Gallery, such a big name. I wasn’t afraid to knock on the door and say, “We need change.” And it happened at a time when people were paying attention, just after Black Lives Matter.

Another thing I noticed is the sense of community around your work. Even scrolling through your page, there’s this spirit of collaboration; you post about other photographers, artists, and even friends’ exhibitions. So I want to know: what does community and collaboration mean in your work? How does it influence you personally, and as part of a wider creative network?

Well, along the way you naturally meet other photographers and artists, and those connections become important. For me, the main collaborations often happen through exhibitions. I sometimes curate, and I’ve always believed that when you bring more than one person together, the message travels further than if you stand alone. So group exhibitions are a form of collaboration I really value.

It’s about sharing knowledge, ideas, and experiences, and I think that sense of connection has been essential to my growth.

I think it’s important to continue these conversations; you’re encouraging newer artists that way. Just to pivot a bit, with your upcoming exhibitions—Me London and Somerset House during the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair 2025—what excites you most about showcasing your art in these spaces?

Two reasons, really, and both connect to my identity. A lot of the time, I ask myself, “Where do I fit in? Am I Spanish? Am I African?” So being included in something like the African Art Fair is an honour. Being invited into that space allows me to ground myself in the African conversation, which is really meaningful.

This will also be my first time exhibiting at 1-54, and I’ll be showing with the Gillian Jason Gallery, which is female-only. That makes it even more special. With Me London, I’m being included in the Spanish conversation as well, which feels important too. Being part of that dialogue gives me a sense of inclusion I’ve struggled with before. Both shows carry deep meaning for me.

I’m very, very grateful.

That’s very exciting. I also wanted to touch on your work with different galleries and clients. You’ve gone from Christie’s to Vogue, you continue to work with celebrities and even film. Does that kind of recognition change anything about your process or practice?

Honestly, I don’t think it does. My practice stays the same. But it does open conversations. I wouldn’t say it automatically opens doors, but it gives me something to talk about. For example, early on I’d say, “I’m building a portfolio.” Later, I could say, “I’ve done a cover for this magazine,” or “I’m exhibiting at Christie’s or the National Portrait Gallery.” Those milestones give you confidence and credibility.

But people don’t just knock on your door because of it. No one has come to me saying, “Oh, you’ve been at the National Portrait Gallery, I want you in my show.” I’m still the one reaching out, sharing my story. The recognition doesn’t change my practice, but it does strengthen my CV, makes people trust me more, and create opportunities for bigger conversations.

I love to see artists like yourself winning. It’s incredible, to say the least. My next question is about your style, especially with the Hand Masters series. You use the Old Masters style, something you’ve said you didn’t connect with at first. But now you’ve transformed it into something of your own. So I wanted to ask about that creative process, how you take something you didn’t originally connect with and make it your own. How do you work through that transformation in your practice?

I didn’t have a plan for it. Some of it came from education; you go to school, you study photography, you learn about Old Master lighting. It stays at the back of your mind. Rembrandt lighting, for example, is just there, and when you start creating, that’s often what you fall back on.

For me, it began when I developed vitiligo. At the time, people suddenly thought vitiligo was “fashionable” and wanted to photograph me. But I didn’t trust anyone to do that, I didn’t want my condition to be treated like a trend. It felt unfair: people saw vitiligo as “cool,” while other skin conditions were still stigmatised. So I decided I had to record myself instead.

I remember seeing an image once, a man lying on a table holding flowers. I tried to recreate it, and that became the first Hand Masters piece. I thought, “This isn’t bad,” so I kept experimenting. The first piece did well, then the second became a Christmas card, and that’s when I realised it was taking the form of an Old Masters style. By the third, I was studying Dutch florals, and suddenly I found myself loving what I used to hate.

That’s when the series really took shape. I kept the word “Masters” deliberately. The Old Masters we’re taught about don’t include African narratives; they’re European, educated in a certain way, and very exclusive. I thought: “Why can’t an African artist create ‘Old Masters’ too?” This is my art, my heritage, and I wanted to claim that space.

I also chose to hide my face and centre the work on my hands. I wanted people to look at my hands, see their beauty, and not just see vitiligo. Adding flowers helped transform them into something healing. I used to be terrified of getting vitiligo on my hands, and when it happened, when they turned completely white, creating the Hand Masters series helped me embrace them. It was a process of both making art and learning to love myself.

Thank you so much for sharing. Since this series will be shown in upcoming exhibitions, what do you hope people take away from experiencing it?

One of my main goals is to break the boundary between photography and painting. As a photographer, you’re expected to be highly technical: to know every detail about cameras, numbers, and lighting setups. But I don’t create from numbers, I create from feeling and emotion.

On the other side, the art world often refuses to see photography as art; if it’s not oil painting with brushstrokes, it doesn’t count. But with my Hand Masters series, people are often confused: is it a photograph, a painting, or even AI? And I like that. To push it further, I print on canvas and paint over the photographs, so no one can box me into one category. I want to occupy both spaces.

For me, the point is that art doesn’t need to be either/or. I’m both a photographer and an artist, and I want people to accept that. As a Black woman, people don’t expect me to be a photographer. I’ve been in studios where I’m holding the camera and people look around asking, “Where’s the photographer?” I am the photographer. I am the artist. Don’t try to reduce my work to one or the other; it’s both, and it’s valid.

It’s the industry that tries to divide and categorise. My art exists in the middle, unapologetically.

Thank you for sharing that. I think artists like you show that it’s possible to resist those limits. To close on a lighter note, you’ve mentioned that photography has taken you to countries you never even dreamed of visiting. What would you say are your top three places you’ve travelled to?

One of the most surprising places for me has been Jeddah in Saudi Arabia. I’ve been going there for four years now, and at first I was terrified, thinking, “Oh my goodness, I’m a Black woman, how will I be treated?” But it’s been one of my favourite experiences. The people were warm and welcoming. They have this beautiful culture of taking care of visitors; you’re in their country, so they make sure you feel safe.

Of course, you have to be respectful, just like I would when visiting Cameroon, and that’s fine. Once I embraced that, I found the experience incredibly rewarding. I realised there’s so much opportunity in Arabic countries. They’re evolving, opening up, seeking new ideas. There’s pride there, and it makes you feel like you belong to a bigger world. It was a real eye-opener.

Thank you so much for sharing. This has been a wonderful conversation.

Member discussion