Every now and then, we come across a creative whose work doesn’t just look good, it feels like something bigger. Jess Kilubukila is one of those people.

Born in the Congolese diaspora and raised in France, Jess didn’t follow the well-worn path into design. His early career was in finance and public policy, with a deep interest in systems, structure, and social impact. But somewhere between corporate spreadsheets and policy briefs, he felt the pull to return to something more tactile, more personal, and more rooted in the cultural traditions he grew up with. Enter Kilubukila, the eponymous design brand that blends modern aesthetics with traditional Congolese craftsmanship, and does so while creating dignified, sustainable jobs for artisans in the DRC.

At the heart of Kilubukila is the Kuba textile — a centuries-old fabric handwoven from raffia palm — reimagined for the now. Each piece is handmade, slow-crafted, and signed by the artisan who created it. It’s not just décor; it’s identity made tangible. We love Kilubukila because it refuses to fit neatly into a box. It’s a design studio, a cultural project, a community space and above all, a living archive of Congolese creativity.

In our conversation with Jess, we talk about everything from his journey into the creative world, to colour as resistance, to what it really means to “formalise” artisan work in Kinshasa. We explore how he’s challenging the global gaze on African design, and what he’s dreaming into existence for the future of Kilubukila.

This interview is for anyone who cares about thoughtful design, cultural heritage, and the power of creativity to build community and shift narratives, especially those in the African and diasporic creative space.

I wanted to start by talking with you about your background, where your creative journey began, and how your upbringing has shaped the work you do now.

A bit about me first: I'm from the Congolese diaspora. I grew up in France, where I studied philosophy, then moved to London to study finance. I went on to work in investment banking for a while, followed by some time in startups focused on digital payments and financial tech. So, I don't come from a traditional creative background, but I’ve always had a strong interest in making and building things. My grandfather was a carpenter, so working with my hands has always felt natural to me.

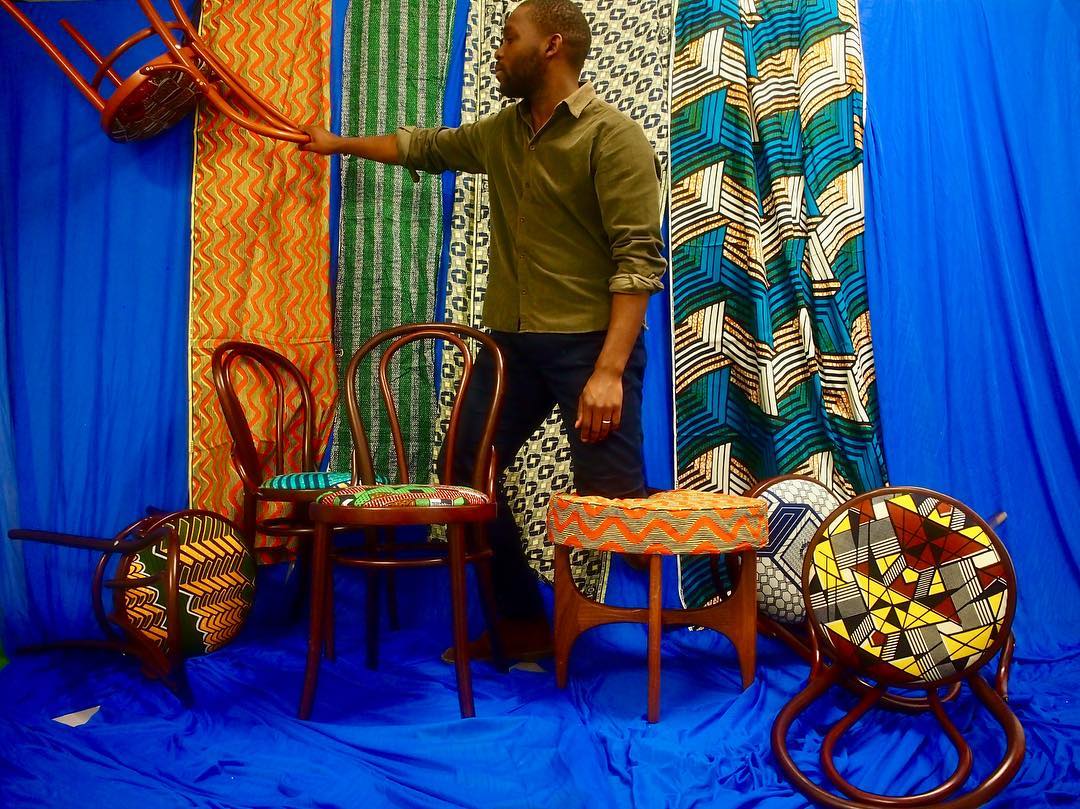

It was actually during my time in investment banking—bored, staring at Excel sheets all day—that I felt the urge to return to creating something tangible. I started learning upholstery, experimenting with classic French Thonet chairs and reupholstering them with African fabrics. I sold them at markets in the UK and got a really positive response.

From there, I started thinking more deeply about Congolese craftsmanship and how I could incorporate those skills and cultural elements into my work. That led me to Kuba textiles, a traditional fabric from the DRC, and the idea of building a product line rooted in Congolese culture. I launched my first collection using Kuba, set up a workshop in Kinshasa, and began collaborating with local artisans not just on textiles but also on furniture. That was six years ago.

Thank you for that quick rundown. I found it especially interesting that you come from a finance background before entering the creative world. Was there a particular moment that pushed you to pursue this path more seriously?

That’s a great question. Actually, I still work part-time in the creative space. The rest of the time, I’m a consultant on public policy in the Congo, focusing on areas like public health, agricultural development and forest preservation. I like having both worlds; it’s like two sides of the same coin. On one hand, I contribute to shaping large-scale social and environmental policy. On the other hand, I get to connect directly with artisans and work on preserving and celebrating Congolese culture through design.

So there was never a dramatic shift; I've always done both and still enjoy that balance. But the turning point came when I decided to move back to Congo. That happened after a major design trade event in Paris, Maison & Objet. I secured a large order from some big French retailers, and I realised it was time to take things more seriously. That was around 2019 or 2020. It also marked the start of my five-year plan to build something more sustainable and impactful.

Did you always plan to move back to Congo permanently, or was it just for the order, and then you'd return? Yeah, I always had it in mind to go back, to settle in and see what it was like. Even before I entered the creative space, it was a long-standing ambition of mine to return and see how I could contribute. I wanted to explore how my skills could align with my ambitions, especially through the lens of being part of the diaspora and giving back in a meaningful way.

That makes sense. I think my next question is, why was it important for you to root the brand in Congolese heritage? You have a mix of different cultural influences, French and British, so why was it important to ground it in Congolese craftsmanship and tradition? What does that mean to you?

For me, before being French or British, I’m Congolese. I come from Congolese traditions. I grew up with Congolese culture. And I think that was the last piece of my identity I hadn’t fully experienced, not just through holiday visits, but by actually living there. I wanted to understand what it meant to be there on the ground; to work, to face the daily challenges like power cuts, water shortages, traffic congestion, the heat, but also to enjoy the beautiful nature, the music, and being surrounded by African people. That was something deeply important to me.

In terms of the brand, I noticed a gap, both in the market and in the aesthetic I was drawn to. I was starting to earn more and began investing in interior design, which I love. But I couldn’t really see myself in the typical “African decor” that was out there. A lot of it felt very colonial in style. I wanted something that felt true to who I am, modern but grounded in tradition. I wanted it to be made by artisans on the continent, something that reflected me as part of the African diaspora. Not fully modern, not fully traditional, just a balance of both. And I think that’s the space my brand is trying to define.

You’ve just perfectly led me to my next question. I was going to ask about your mission to challenge the modern African aesthetic—what that looks like in practice.

I’ll speak from a Congolese perspective, since that’s the one I know best. Colonisation hit Congo very hard, so much so that we’ve almost forgotten what pre-colonial life looked like. We're still in the process of reclaiming our values, which includes redefining our aesthetic and how we see one another.

What I’m trying to do is dig into traditional Congolese craft, culture, and art, and use that to create modern products, pieces that appeal not only to Congolese people but also to an international audience.

I think this tension between tradition and modernity is powerful. It could be the key to finding our identity again and to restoring pride in Congo. Just this morning, I was talking to another creative who makes beautiful soaps. She asked me, “Where is your main market? Who buys your work?” And we came to the same conclusion: unfortunately, Congolese people aren’t buying our products at the level we’d hope, even though we’re trying to elevate Congolese culture.

So part of our mission is to change that. I want to support and invest in beautiful, well-made products from Congo because I’m proud of them, because they reflect who I am. And I believe that’s the mission we, as Congolese creatives, need to take on.

You mentioned something earlier about the tension between past and present, tradition and modern aesthetics. How do you approach that creative tension? How do you make sure you're balancing both?

I think an easy answer is that I use traditional making processes but incorporate more modern aesthetics. For example, with my leading products, cushions and rugs, I use traditional Kuba textile techniques, but I'm introducing new objects, new patterns, and new designs. So the products speak to someone who’s drawn to tradition, they’ll recognise the textile, but they also speak to someone with a broader or more contemporary perspective because the designs are more modern, the colours are different. So in our creative process, that’s where the modernity lies. But when it comes to the making itself, I try to be more conservative because I think it's important to safeguard our traditions.

Let me expand on that a bit. You mentioned colour as a way you bring in modernity, and I know it plays a vital role in your collections. What’s your process for choosing colours? Where do these palettes come from? Is it something that comes naturally to you?

Most of the colours we use are natural, though unfortunately, not all of them. I try to use what’s around me. So I work with local skills and natural pigments when I can. For example, I’ll use charcoal for black, certain roots for yellow and brown, etc. It means I often have to work with a limited palette, and that’s fine, but I do also import some pigments. For instance, blue isn’t something I can source locally in the DRC, so I import it. My colour choices really come from what’s available to me and what resonates with me personally.

I see. When you started the brand, did you always know you wanted to work with colour? Why did you go that route, especially now when minimal aesthetics are so popular?

Yes, I’ve always loved colour. I think interiors should reflect personality. Monochrome spaces feel a little boring to me. There’s no point in having a home that looks like everyone else’s. When you use colour, you're making bold choices. You're expressing yourself more clearly and honestly. For me, colour represents being bold, not shy, being proud of who you are, and I think that has to be expressed visually. If you look around in Africa, in the DRC, for example, people wear colour in their clothes. They wear bold prints. It’s colourful outside too: the flowers, the greenery... So why shouldn't our interiors reflect that vibrancy?

I completely agree. You mentioned that you work with artisans across the DRC. What has that journey of collaboration looked like for you, and what has it taught you?

It’s been a difficult journey. When I was in London, my job was completely different. I was mainly focused on the creative process, ensuring product quality and design. But when I moved back to Congo, everything changed. I found myself much more involved in project management and organisational challenges. You become the person who solves problems; your artisan has a family emergency, their child is sick, or you’re waiting for raw materials that were supposed to arrive three weeks ago with no word from the supplier.

All of this makes building a business on the African continent, and in the DRC in particular, much harder. So, unfortunately, I’ve had to become more of a problem solver than a creative.

Absolutely. These are challenges many entrepreneurs face across Africa. On your website, you mention “formalising artisans.” I’d love for you to unpack what that means and what kind of impact you're hoping it will have.

One of the brand’s main goals is to create economic opportunities for the artisans we work with. In Congo, the creative industry is very informal. Many artisans operate in what you might call the "dark market"; they don’t have official status, formal training, or even a proper workspace. Their conditions are extremely precarious.

What we’re trying to do is offer structure and support. We provide a shared workspace, textile-making training, some sales and marketing skills, and even medical and financial support. If an artisan wants to launch their own product line or business, we try to equip them with the tools to do so.

The goal is to help them transition from informal workers to creative entrepreneurs by filling the gap left by both government and private sector support.

That’s amazing. And have you started seeing the impact of this over the years?

Definitely. The most visible impact has been on the artisans within our workshop. We've seen people grow from entry-level artisans to heads of departments like quality control. Some have been able to pay their children’s school fees all the way up to university, which is something we’re really proud of.

We’ve also expanded our program from working with just six artisans at the beginning to now collaborating with about 60. That’s a big win for us.

Community is a huge part of what we do, so I’m curious — how would you say your vision is shaped by community, and how does that influence your brand?

I think community is absolutely central to what I do. The work we create is for the community and made by the community. It's a deeply identity-driven process both in how we design and in the final product itself.

Our pieces are created collaboratively, and we make it a point for each maker to sign their product. That way, the person who receives it knows exactly who made it. We don't want our products to be anonymous. We want people to know that Margaret in London bought something crafted by Maman Helene in Kinshasa.

Another core part of our mission, which I’ve spoken about before, is to create economic opportunities. One of the atelier’s main goals is job creation. I believe giving people a way to earn a living by making something they’re proud of — something rooted in their identity and culture — is one of the best ways to support a community.

And because they’re part of that community, the income they earn gets reinvested in it. It supports their families, their surroundings. That’s why our workshop isn’t based in central Kinshasa, where the wealthy live, but rather closer to where artisans actually reside in the suburbs. We want them to feel comfortable, connected to the work, and empowered by the process.

We also show them where their work ends up. We’ve had pieces go to the Brooklyn Museum in New York, for example, and we share photos with them so they can see their craft reaching places and people they may never have imagined. It’s about making a very local process feel globally relevant and deeply connected.

That makes perfect sense. On your page, there’s a recurring theme around slow living and slow design. I’d love to hear more about why that’s important to you and what it really means in the context of your work.

It’s honestly at the heart of everything we do. We're working with culture, with identity-based products. We’re not here to mass produce or make things that don’t carry meaning.

We want our artisans to work in dignified conditions, using local materials and dyes whenever possible. We want our process to respect the environment and the people involved. To us, caring for the people and the planet is inherently African. It’s a way of life that reflects respect for the community, because no community can exist without its environment.

That’s why this philosophy is so foundational to the brand. It was also recognised when we partnered with the UNDP and contributed to the Sustainable Development Goals, showing that a model of production grounded in culture and ecology can, and should, be a viable business model.

I couldn’t agree more, especially in this age of fast fashion and mass production. I think it’s so necessary to slow down.

Another question I had is: What do you personally hope the world will unlearn about African design? And in turn, what should we relearn about African design and craftsmanship more broadly?

One thing I really hope the world unlearns is this idea that African design is primarily meant for export — that it’s made only for Western consumption. African design isn’t tribal or stuck in the past; it’s dynamic, intellectual, and ever-evolving. The world must unlearn the idea that it’s only valuable when reinterpreted through Western eyes. That’s the kind of mindset that kept African design stuck in a sort of colonial aesthetic for too long.

Now, I think it's time to shift that. We should be learning how to embrace slow living, how to value our own quality of life, starting within our homes. Our spaces should feel beautiful, natural, and respectful, not just of aesthetics but of our environment and our makers.

But most importantly, design should be made on the continent. We need to uplift and invest in our own traditions and our own creativity, not just as a heritage, but as a living, evolving practice. We need to relearn that African design holds deep knowledge: in symbols, in structure, in sustainability.

It’s contemporary, rooted, and forward-thinking all at once. There’s no single aesthetic, just a rich, plural tapestry.

We should also move away from extractive economic models and toward ones that centre local production and consumption. Respecting ourselves and our culture means living well in our own spaces. You don’t need to be wealthy to feel comfortable. Comfort doesn’t have to be a luxury; it can be cultural. We need to relearn that what we produce and what we live with should reflect our values, our environment, and our communities.

What are you dreaming into existence for KILUBUKILA over the next few years?

We’re building Kilubukila into a multidisciplinary creative studio where design meets education, culture meets innovation. A space that trains and employs local artisans, especially women and youth, with dignified, skilled work.

Our goal: to become a globally recognised textile and interior design house rooted in Congolese excellence. More than a brand, Kilubukila will be a home for creativity, heritage, and community impact.

Thank you so much for sharing your story with us!

Images via @kilubukila

Member discussion