There's something special about music that runs in families. Not the kind you learn from school or online videos, but the kind that gets passed down from parent to child, almost like it's in the blood. In Africa, where stories and history have always been kept alive through song, some families haven't just made music, they've become the music itself.

These aren't just stories about famous musicians. They're about families who survived impossible odds, who kept playing through dictatorships and exile, and reinvented their sound for each new generation while keeping the heart of it intact. They carried Africa's music from small villages to the biggest stages in the world. And in a time when everything feels temporary, these musical dynasties just keep getting stronger.

The Kutis

If music could be rebellion, the Kuti family would be its generals.

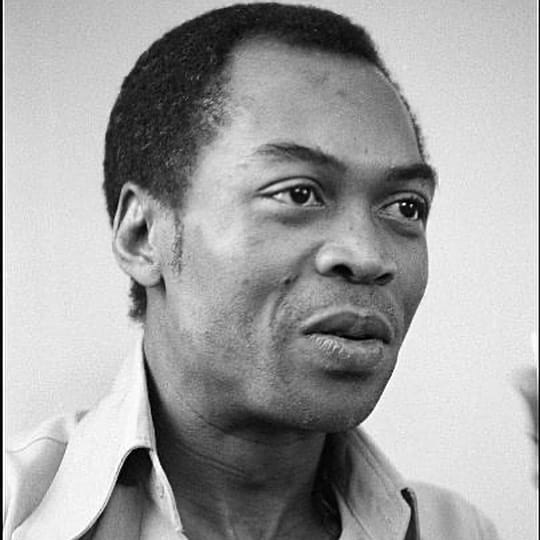

Fela Anikulapo Kuti was born in 1938 into a household already deep in resistance. His mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, led women's revolts and won international peace prizes. But Fela wasn't interested in becoming a doctor like his parents hoped. He went to London to study medicine and came back with a trumpet and a vision.

In the 1960s and 70s, Fela created Afrobeat, a wild fusion of jazz, funk, highlife, and traditional Yoruba music. But Afrobeat wasn't just music. It was a weapon. Songs like "Zombie" mocked the military so effectively that soldiers raided his compound, threw his 82-year-old mother from a window, and beat him senseless. They burned everything. And still, Fela kept playing.

When Fela died in 1997, many wondered if Afrobeat would die with him. They hadn't met his sons. Femi Kuti had been playing saxophone in his father's band since he was 15. In 1986, he formed Positive Force, shortening the marathon songs while keeping the political fire. Five Grammy nominations followed. In 2010, he played at the World Cup opening ceremony, bringing Afrobeat to nearly a billion viewers.

Seun Kuti, the youngest son, inherited Egypt 80 at just 14 when his father died. Where Femi carved his own path, Seun became the keeper of the legacy, keeping his father's longer song structures and confrontational style. He also led protests and revived his father's political party.

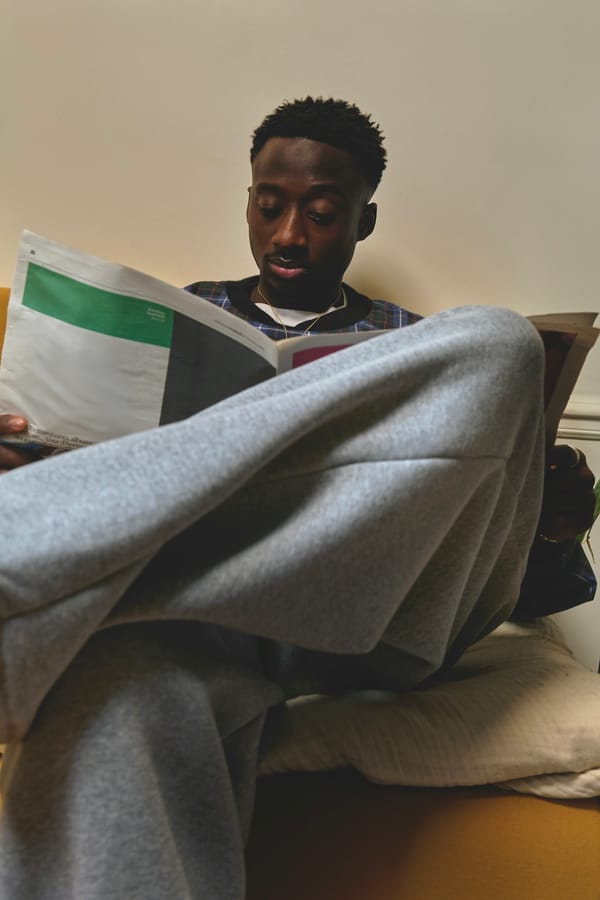

Now, a third generation has arrived. Made Kuti, Femi's son, studied at the same London institution where Fela studied decades earlier and plays every instrument you can name. In 2021, he and his father released a double album, Legacy+. The Grammy nomination made him the third generation of Kutis to be recognized.

The Kuti family hasn't just preserved Afrobeat, they've kept it alive, growing, and dangerously relevant.

The Makeba-Masekela Legacy

Some dynasties are built through blood. Others are forged through shared struggle and brief, brilliant love stories that echo across generations. Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela were married for only two years in the mid-1960s, but their separate journeys shaped South African music forever. Both were forced into exile after apartheid stripped them of their passports. Both used their voices as weapons against injustice.

Miriam Makeba, "Mama Africa," left South Africa in 1959. Her songs "Pata Pata" and "The Click Song" introduced the world to Xhosa and Zulu languages. She sang at John F. Kennedy's birthday, testified against apartheid at the United Nations, and won a Grammy in 1965. But when she married Black Panther activist Stokely Carmichael in 1968, America turned its back. She spent the next two decades touring the world, unable to return home until Nelson Mandela personally invited her back in 1990.

Her granddaughter Zenzi Makeba Lee has emerged as a vocalist in her own right, performing her grandmother's songs and keeping that distinctive Makeba vocal style alive.

Hugh Masekela got one of his first trumpets as a gift from Louis Armstrong himself, and by his teens, he was already a virtuoso. But the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre made staying in South Africa impossible.

In exile, his 1968 instrumental "Grazing in the Grass" hit number one in America; the first African musician to top the US charts. His 1987 anthem "Bring Him Back Home" later became the soundtrack to the movement to free Mandela.

Hugh’s son, Selema "Sal" Masekela, became one of America's most recognizable sports commentators. He also carried on his father's musical legacy, performing as a musician as part of a band called Alekesam, named after his father.

When Hugh died in 2018, tributes poured in from around the world. But one of the most fitting things about him was this: despite having the open arms of many countries during his exile, he refused to take citizenship anywhere but South Africa. He knew he'd come home eventually, and he did.

The Diabaté Dynasty

Imagine if you could trace your family tree back over 70 generations. Not through documents or DNA tests, but through an unbroken chain of fathers teaching sons music passed down across centuries.

That's the Diabaté family. They are griots, the hereditary musicians and storytellers of West Africa's Mandé people. For them, music isn't a career choice. It's a birthright that stretches back to the Mali Empire. And their instrument is the kora, a 21-stringed harp-lute that sounds like water and light having a conversation.

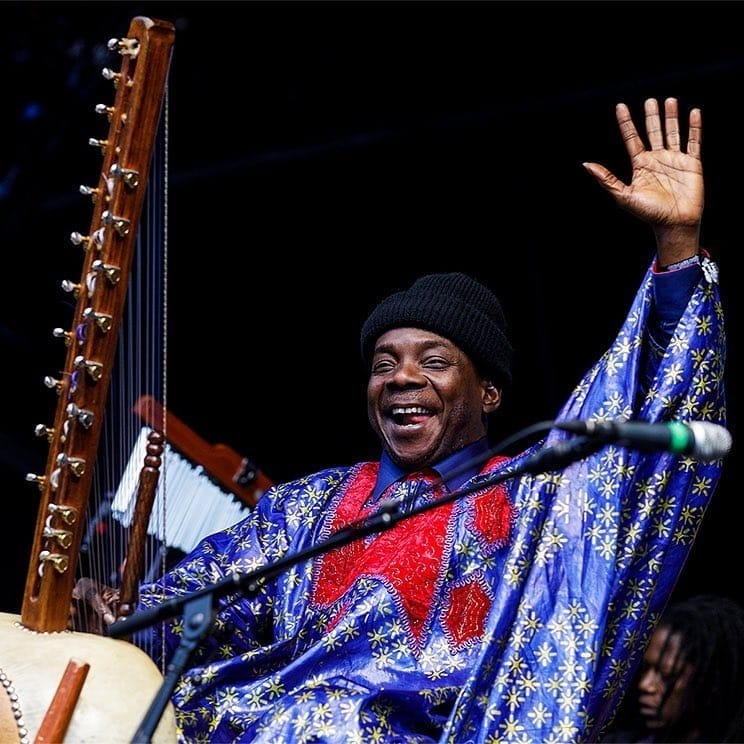

Sidiki Diabaté Sr., born in 1922, took the kora from courtly ceremonies to recorded music. In 1970, he released Mali: Ancient Strings, the first album to feature the kora exclusively. He became known as "The King of Kora." His son Toumani Diabaté, born in 1965, took his father's revolution to the world stage. Interestingly, Toumani never received a formal lesson from his father, he learned by watching and listening. By age 13, he was performing publicly. By his twenties, he was being called the greatest kora player alive.

Toumani didn't just master tradition, he exploded it. He recorded the first solo kora album in 1988. He collaborated with Taj Mahal, Björk, flamenco guitarists, and the London Symphony Orchestra. He won two Grammy Awards, and his album with Ali Farka Touré, In the Heart of the Moon, is considered a masterpiece.

In 2014, Toumani recorded an album with his eldest son, Sidiki Diabaté Jr. called Toumani & Sidiki, a kora duet that was something of a passing of the torch. But Sidiki Jr. represents something new. Yes, he's a kora virtuoso. But he's also one of Mali's biggest hip-hop stars, filling 20,000-seat stadiums. He runs his own recording studio alongside rapper Iba One, and was voted Mali's best beat maker in 2013.

Toumani passed away in July 2024 at age 58, but the dynasty continues. Sidiki Jr. stands as the 72nd generation, proving that a 700-year-old sound can still shake stadium speakers.

The Jobarteh Family

When you come from one of West Africa's principal kora-playing griot families, and your grandfather was the legendary Amadu Bansang Jobarteh, you're born with a legacy carved in stone. When you're also a woman, that same legacy becomes a wall.

Sona Jobarteh crashed through it.

Born in London in 1983, Sona grew up between two worlds. Her father, Sanjally Jobarteh, is a master kora player from a griot dynasty tracing back to the 13th century. The Jobarteh family has guarded the kora tradition for hundreds of years; fathers teaching sons. Not daughters. Never daughters.

But Sona learned anyway. She started at age four, taught first by her older brother, then by her father. While learning kora at home, she studied cello, piano, and composition at London's Royal College of Music. At 17, she traveled to Norway to challenge her father to teach her properly. They spent four years in intensive study.

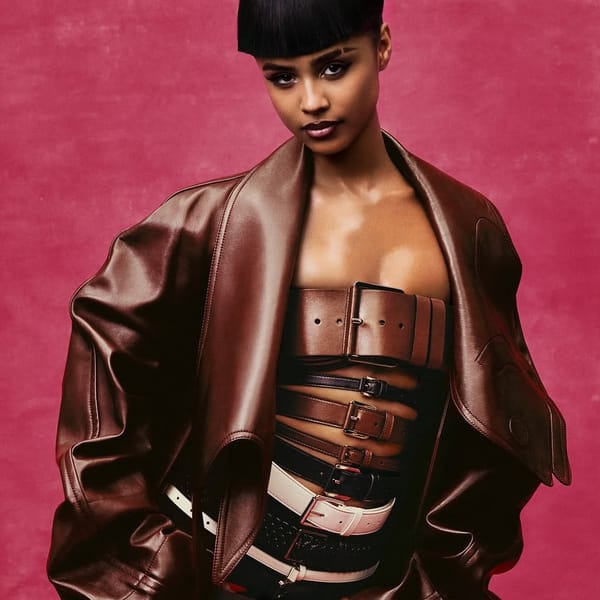

Her 2011 debut album Fasiya announced her arrival as the first female kora virtuoso from the griot tradition. But she didn't stop there, she reimagined it, incorporating electric guitar, drums, and jazz. Her 2022 album Badinyaa Kumoo pushed further, featuring collaborations with Youssou N'Dour.

Today, Sona headlines festivals worldwide; Glastonbury, WOMAD, the Hollywood Bowl. Berklee College of Music awarded her an honorary doctorate. But perhaps her most revolutionary act is the Gambia Academy, which she founded in 2015. It teaches students kora, balafon, and drumming alongside math and science. And crucially, there are no gender restrictions. Boys and girls learn kora side by side.

She didn't just become the first woman from a griot family to master the kora professionally. She became a blueprint for what happens when talent and determination meets the courage to rewrite ancient rules.

The Touré Dynasty

Ali Farka Touré came from a noble lineage, which in traditional Malian society meant music was forbidden to him. Music belonged to griots. But Ali didn't care. As a child, he secretly built instruments and taught himself to play. He later created "desert blues,” a fusion of traditional Malian music with sounds that felt like American blues.

His breakthrough came in the 1980s and 90s. In 1994, he recorded Talking Timbuktu with American guitarist Ry Cooder. It won a Grammy. His collaboration with Toumani Diabaté, In the Heart of the Moon, won another. When he died in 2006 at age 66, an entire nation mourned.

His son, Vieux Farka Touré, born in 1981, is often called "the Hendrix of the Sahara." Ali had initially opposed his son's music career, even sending him to the army for military training. But Vieux couldn't stay away. He started secretly learning guitar in 2001. With help from Toumani Diabaté, Vieux eventually convinced his father to give his blessing. Ali died just months after they recorded together.

Vieux didn't simply recreate his father's music, he brought it into the 21st century. His albums layered in rock, Latin rhythms, reggae, and dub. In 2022, he teamed up with Texas trio Khruangbin for Ali, a reimagined cover album of his father's songs that introduced Ali Farka Touré to a generation who'd never heard of him.

Beyond music, Vieux founded Amahrec Sahel, a nonprofit providing musical instruments for children in Mali. The country has been torn by conflict for over a decade, but through it all, Vieux has remained committed to keeping Mali's musical heritage alive.

The Dube Dynasty

Growing up in apartheid South Africa, Lucky had every reason not to be fortunate. His family was poor. He worked as a gardener while trying to stay in school. But Lucky discovered he could sing. He started in school choirs, then joined local bands playing mbaqanga. At 18, he signed with Teal Records.

Then Lucky discovered reggae. Inspired by Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, he realized that reggae's messaging about oppression and liberation mapped perfectly onto South Africa's situation under apartheid. He then decided to switch genres entirely.

In 1984, Lucky recorded Rastas Never Die but the album failed, selling only 4,000 copies. The apartheid government banned it in 1985. His label told him to return to mbaqanga. Instead, Lucky went back into the studio and secretly recorded Think About the Children. It went platinum.

From 1985 until his death in 2007, Lucky released 22 albums. He won multiple awards, signed with Motown in 1996, and was named "Best Selling African Recording Artist" at the World Music Awards. He performed at Live 8 in Johannesburg and became the voice of a generation. Countries across Africa celebrated his birthday as a national event.

After his death in 2007, his children Thokozani (TK) and Nkulee carried on his legacy. TK occasionally performs with the Lucky Dube Band, keeping his father's music alive globally. He also founded Different Colours Productions, helping emerging artists navigate the music industry. He later earned an MBA, combining his IT career with his passion for supporting musicians.

Nkulee has created her own path, blending "ethno-ragga" with soul and jazz. In 2014, she became the first non-Caribbean entertainer to receive seven nominations at the International World Reggae Music Awards, winning "Most Promising New Entertainer."

The Dube name carries weight everywhere reggae is played. And through TK and Nkulee, the music continues into a new generation.

Conclusion

These families didn't just shape African music. They showed the world what African music really is; not a style or a genre, but a living conversation across generations, a refusal to be silenced, and a promise that the sound will continue long after we're all gone.

Member discussion