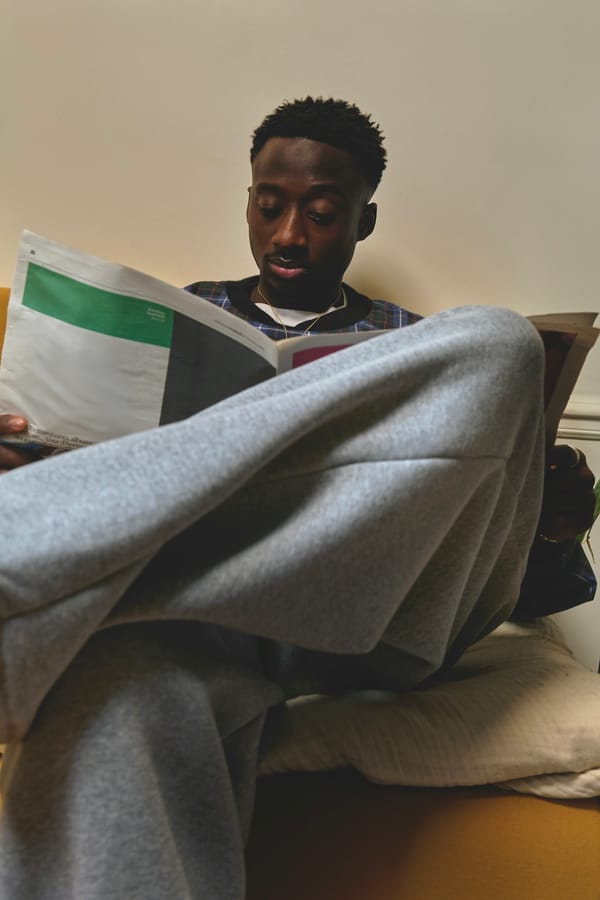

Onyeka Igwe is a London-born moving-image artist and researcher whose work explores how we live together, drawing on the archive, the body, and everyday Black life to illuminate overlooked histories. Known for her rhythmic editing and sensorial approach to storytelling, her films have screened at MoMA, ICA London, Dhaka Art Summit, FESPACO, and major festivals worldwide. She has held solo exhibitions at MoMA PS1, LUX, Peer, and Mercer Union, and has earned nominations for the Jarman Award and Max Mara Artist Prize for Women, among others. She opens a solo exhibition at Tate Britain in 2025.

This winter, Onyeka leads Visions in the Nunnery – Programme 2 at Bow Arts’ Nunnery Gallery, presenting her acclaimed film “the names have been changed, including my own and truths have been altered (2019)” alongside 24 international artists exploring memory, narrative, identity, and the archive.

In our interview, we discuss her curatorial approach, the global resonances across the selected works, what it means to revisit a deeply personal film years later, the role of rhythm in her editing, and the significance of showing this work in her hometown at a pivotal moment in her career.

The exhibition brings together 24 international filmmakers and artists, and I wanted to touch on your approach to curating such a diverse group of people. What qualities or themes would you say connect their work, and also connect their work to yours?

There was an open call for the program, and each program has a lead artist. I was the lead artist for this one, and people were responding a little bit to some of the themes and elements of my own work. Some of the things we were interested in exploring and highlighting were memory, identity, and the archive, because those are key for me. Also thinking about narrative, working with narrative, reworking narrative, and experimenting with narrative, because those are all features of my own practice. So we were trying to pick artists who worked within those themes in a way that would make sense in an exhibition.

I know that archiving and memory are also a big part of your work. Your film also explores colonial archives, family, and memory. So, how do you think showing it within this collective context changes or expands the conversation around the film?

I think that showing something in relation to other works can really highlight and bring out some of the ideas and themes, and allows you to see the work in a different way. I made the film, the names have changed, including my own and truths have been altered, in 2018–2019, so it’s about six years old now. A lot has changed. For me, it’s interesting to revisit it alongside newer works and different artists, and to see how some of these ideas around memory and identity have been taken up by other people. It gives a boost, or a new perspective, to my own work.

Yeah, that makes sense. Visions in the Nunnery has long been a platform pushing for experimental moving image and experimental art. What does it mean to you to be leading this program—Program 2—at this particular moment in your career, especially following some of the other milestones you’ve had?

I like to show my work in different contexts, and I’ve known about Visions for quite some time. It’s local to me, part of the area I grew up in in London. And I always like to show work in places that don’t necessarily attract the same crowd. Visions has a long history; people have been going for many years, especially people from that area. It’s also integrated with the University of East London; students there engage with the program and make their own work. So I think it’s a great opportunity for people to engage with my practice and the practices of other artists outside of these bigger institutions.

One of the first things I noticed is how different the exhibition is, and how accommodating it is of people with styles that are not exactly mainstream. And on the artists in the program, many of them are early in their careers or just emerging. How do you see your role in nurturing and amplifying the new generation of filmmakers and moving-image artists?

I don’t know if I have a definitive role, but I’m always open to engaging with artists who are emerging or newer and sharing my experiences. I’m appreciative of having these conversations. When I was starting out, people helped me a lot by sharing their experiences, so I’m always up for doing the same.

The exhibition spans many geographies, many countries, and also personal histories; Nigeria, Ukraine, Argentina. What have you discovered, as you’ve been putting all of this together, about resonances across these international works?

I think it’s funny, one of the films that came through had a similar name to a film I made in the past. It’s by an artist called Emery Joan, and their film is called We Will Learn to Call Ourselves New Names. And I had a film a few years ago called We Need New Names. You know, it’s based on a book. So I think I can see a similarity; people thinking along similar lines, using similar strategies to engage with feelings of loss or distance or diaspora. And that comes from so many different communities that people are employing these similar approaches. For me, that’s comforting in some way, that across geography, there’s a moment in which we can meet, a kind of zone of contact, and that comes across in these film works. So I’m really excited to see all the works in the space, meet some of the filmmakers if they’re around, and just see what the resonances are when the works are actually in the space.

Congratulations on the opening. You have your own films and your own work showing as well, and your editing style is known specifically for being rhythmic and for the play between image and sound. So, what do you think about rhythm and dissonance within a collective context? Is it a form of choreography for you, or can it be everyone moving in their own sort of rhythm? I’d just like to hear your thoughts.

I think that internally in the films, there’s a specific kind of rhythm to the editing and to the relationship between sound and image. Sometimes I’m interested in creating dissonance, sometimes it’s a different type of relationship between the two. But for me, it’s that interplay that produces a kind of effect; a feeling, a reaction, and meaning for the audience, for the viewer. And then when that happens in space, it’s a different thing. And you’re right that people bring their own rhythm; how they move around the space is something I can’t control. And that helps them engage with the work differently. I’m really interested in those things: choreographing space, movement, and how that can activate moving image. And how breaking up the sound and image portions of a film can allow the audience to create their own rhythm. For me, that’s an experiment, it’s an open question, and I’m curious to learn from other people about what that creates for them.

That’s interesting. Coming from that, can you take us through your creative process a bit? Do you start with an idea? Do you start with a rhythm in mind? Or do you start with an image?

I think I start with a question; something I’m curious about, something I want to learn more about, something I want other people to help me puzzle through. And then I also have a kind of formal curiosity as well: something within the structure of cinema or the structure of art that I’m interested in testing out a bit more. So those two things come together, and that’s how the idea develops. So yeah, it’s usually not an image in particular. And the rhythm comes later. The rhythm of the edit is very intuitive in the moment of editing. When I have the images and sounds together, that’s when I figure out what the rhythm of the piece should be. And yeah, it’s something I sense rather than something I’m very prescriptive about.

Thank you for sharing. Curiosity definitely is a big tool for creatives and artists, and I love that that’s your first step. What would you say is your creative process in documenting and archiving?

In documenting and archiving, I try to be very open to anything that comes to me in the moment. I try to pay attention to my encounters with history, and to how all my senses react to something. So maybe I’m in an archive, reading about something, and it’s reminding me of food, or of an experience I had in a different place at a different time. I try to make notes of that, like writing a kind of diary of these experiences, so that when I come back to this material or research to make work, those experiences also come out in the work I’m making.

That makes sense. Thank you. Going back to the exhibition now, I know London’s film and moving-image community has grown immensely over the years. What does it mean to you to present your work in your hometown at a time when artistic film is gaining visibility?

It’s always special to show work where you live because it means the people you engage with, people you’re in community with, family, friends, can see it, can talk to you about it, and it can spark conversations. And yes, as you said, there’s a really vibrant film community or artist moving-image community in London that can also see my work. And you know, I got an email earlier this week from someone who had seen my work at Tate and wanted to share their experience and reflections. I find that those things are much more likely to happen where you live. And who knows where that conversation could go with that person, because it’s possible to start things from those small observations or small connections. And the person who emailed me was a filmmaker. So for me, that’s what I really value about showing where you live. Equally, showing in Nigeria is something I’m really curious about and want to pursue, because a lot of my work is thinking about Nigeria and thinking about my relationship to it. So I’m very curious about the conversations that could be had there as well.

Yeah, it’s great to get feedback from people who connect directly with your work and might even have known you for a long time without you knowing them. My last question to round off will be: when people see your work, when they see this exhibition and the works of the other artists, what would you like them to take away from the experience?

I don’t have any set ideas about what I want people to take away. I just want people to think, to think deeply about the issues or ideas or concepts that the works contain. Or for them to feel something about the works, and for that impression to linger. For it to stay with them a little longer and create some kind of movement or effect in their life. That’s what I hope for.

Thank you very much.

Member discussion