The first thing you notice is the music, that loud blend of juju guitars and talking drums that pours through compound walls and into the street like an open invitation. Then comes the smell: jollof rice battling it out with fried rice, while pepper soup bubbles somewhere nearby, making your mouth water.

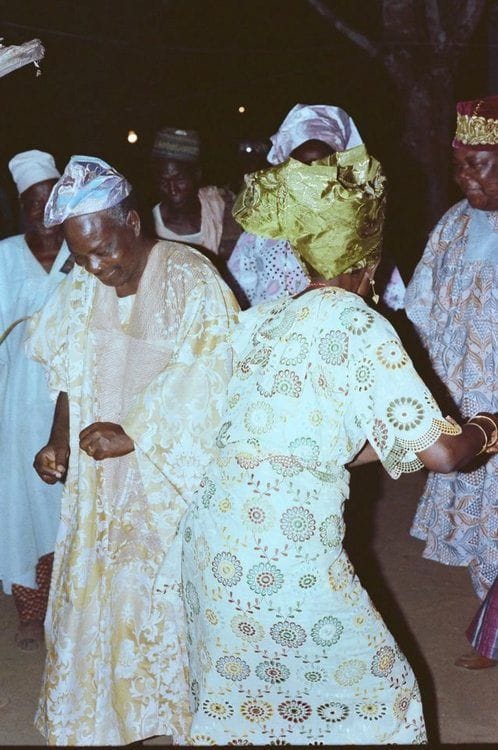

You're eight years old, holding on tight to your mother's wrapper as she weaves through a crowd of aunties and uncles all dressed in the same fabric; matching lace that turns everyone into one big, colourful family.

Someone's getting married. Or buried. Or celebrating their fiftieth birthday. The reason doesn't matter as much as being there together.

This is Owambe. This is home.

How Parties Became Our Culture

The word "Owambe" doesn't really translate to English, and maybe that's perfect. It comes from Yoruba and literally means "it is there,” a simple phrase that grew to mean something much bigger.

By the 1980s and 90s, Owambe had grown from traditional celebrations into something uniquely Nigerian: big parties where your standing in the community was measured by how many people showed up, how much food was served, and how much money was sprayed in the air.

But long before Instagram made aso ebi go viral, Owambe was quietly doing important work; holding communities together. These weren't just parties. They were how we survived, celebrated our success, and found joy together in a country that often asked us to be strong more than it gave us reasons to smile.

The money sprayed at weddings helped newlyweds start their lives. Burial ceremonies honoured the dead while raising money for families left behind. Naming ceremonies welcomed babies into a community that promised to watch over them. Yes, it looked dramatic—naira notes raining down on dancers while Wasiu Alabi Pasuma or Obesere performed. But it was also about sharing. You weren't just giving money; you were showing up for people who mattered to you.

It was a simple way of saying, I stand with you, I celebrate with you, I am part of this family. That sense of togetherness was the heart of Owambe.

Owambe: Then and Now

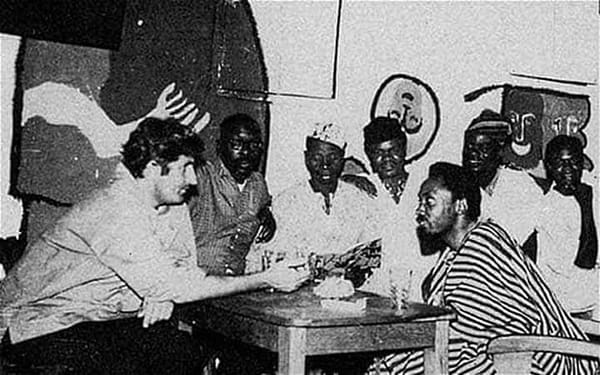

Over the years, Owambe has changed, but it has never lost its spirit. In the 1960s and 70s, it was all about highlife music and juju bands like King Sunny Ade, but today, it’s Burna Boy, Wizkid, and Asake filling the speakers.

Now, there are professional event planners, photographers, and elaborate decorations. Davido might even perform at your wedding if you can afford it. Everything is bigger, fancier, more expensive. Instagram and TikTok have given Owambe a new stage, where the gele tutorials, the makeup, and even the spraying of money are shared all over the world. But no matter how modern it looks now, the feeling is the same: joy and unity.

Today, you’ll find Owambe not only in Lagos or Ibadan, but also in London, Houston, and Toronto. Nigerians abroad carry it with them, turning banquet halls and backyards into little pieces of home. And in that way, it’s become part of a bigger story, one of African culture, identity, and tradition finding new life across continents. Just like gospel, jazz, carnival, or hip hop, Owambe is proof that celebration is also heritage.

That’s why this Black History Month, as part of Marmalade Collective’s Beyond Black: No Place Like Home campaign, we’re honouring traditions like Owambe that tie us together and remind us that culture isn’t something distant in history books; it’s right here, in the music we dance to, the meals we share, and the ways we celebrate each other.

Because at its heart, Owambe isn’t just a party, it’s a reminder that no matter where we go, there’s truly no place like home.

Member discussion